Women in Prison Paying for Their Periods

In 2017, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons issued a memo requiring all federal lockups to provide female prisoners with feminine hygiene products. The BOP announced the move after U.S. Senator Kamala Harris introduced a bill, the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act, to force federal prison officials to offer prisoners free tampons and pads.

Before last year’s change, BOP policy only said that prisons had to make the hygiene products “available.” Tampons and pads didn’t have to be free under the policy, so the feds monetized women’s periods. The vast majority of states charge inmates for feminine hygiene products, although a small but growing number of states provide them for free.

In Arizona, a story similar to that of the Dignity for Incarcerated Women Act unfolded this year. In February, AZ Rep. Althena Salman (D-Tempe) introduced a bill that would require state prisons to give women unlimited menstrual products.

When Rep. Salman introduced her bill, prisons gave locked up women 12 free maxi pads each month. Inmates could only be in possession of 24 pads at a time. If a woman needed more pads, she would have to make a formal request and pay for them. Tampons were, and still are, not free.

According to Salman, an AZ inmate had to work 21 hours to be able to afford a box of 16 pads, or 27 hours for a box of 20 tampons from the commissary. This generally means that inmates’ families foot the bill for basic needs.

But soon after Salman introduced HB 2222, Rep. T.J. Shope (R-Coolidge) shot down the bill, saying that the AZ Dept. of Corrections could handle the problem on its own. Shortly thereafter, the DOC announced it would provide free tampons to inmates, and boost the number of free pads from 12 to 36.

In California, the state’s Administrative Code says that every female inmate must be “issued sanitary napkins and/or tampons as needed.”

In almost all CA counties, including Los Angeles, that means women are given pads and charged for tampons, but at least two counties—San Francisco and San Mateo—reportedly provide free tampons. While LA County doesn’t provide free tampons to jail inmates, the LA County Board of Supervisors voted in January to provide youth in probation camps with tampons, after the locked up girls complained of flimsy pads and paper underwear, among other hygiene issues.

Prison Commissary Problems

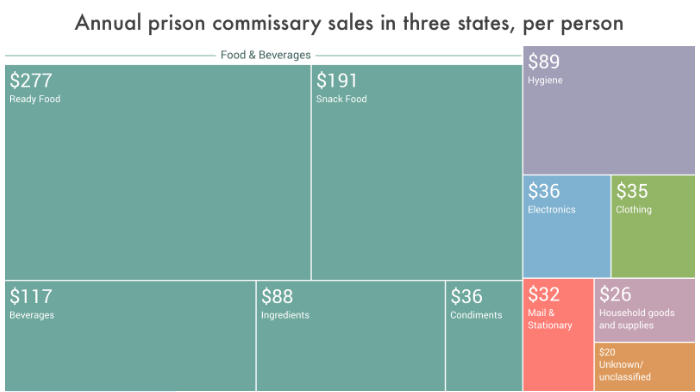

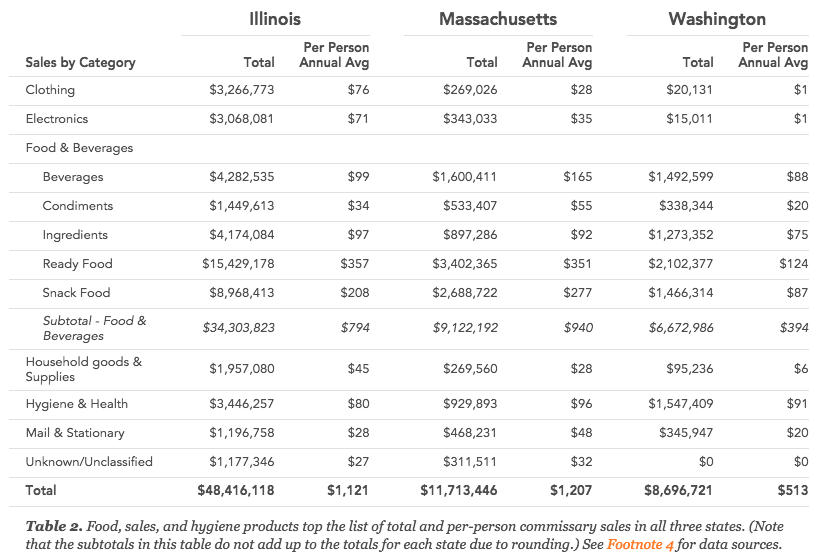

A new Prison Policy Initiative report examining prison commissaries revealed that after food and beverages, which accounted for 75% of all commissary purchases, inmates (and their families) spent the most on hygiene products.

PPI’s researchers looked at data from three states: Illinois, Massachusetts, Washington. The trio of states had easily accessible commissary data and represented a range of prison population sizes and had both state-run and privately run prison commissaries, according to the report.

In addition to food, beverages, and toiletries and other hygiene products (like tampons, shampoo, and toilet paper), prison commissaries offer inmates clothing, mailing supplies, electronics, digital products (like music streaming, games, and email services), over the counter medicines and vitamins, and more.

Inmates in the three states spent an average of $947 on commissary items in a year, a figure far above the $180 to $660 that the average prison worker makes in a typical year, according to the report.

This means that inmates’ families are picking up the tab for commissary purchases, along with the cost of phone calls, money transfers, medical co-pays, and other charges that can add up to hundreds of dollars a month. (At the same time, inmates’ husbands, wives, and children often suffer the loss of their incarcerated loved one’s income.) Inmates whose families do not send them commissary money must rely on their prison jobs to cover their needs, or forego the commissary items.

The report said that the fact that 75% of inmates’ spending went to food and drinks indicated “a widespread need to supplement the food” that prisons serve inmates.

“Prison and jail cafeterias are notorious for serving small portions of unappealing food,” the report says. “Another leading problem with prison food is inadequate nutritional content. While the commissary may help supplement a lack of calories in the cafeteria (for a price, of course), it does not compensate for poor quality. No fresh food is available, and most commissary food items are heavily processed.” So inmates buy tons of snack foods and ready-to-eat meals. This is unsurprising, the report says, because “many people need more food than the prison provides, and the easiest—if not only—alternatives are ramen and candy bars.”

Inmates are generally not spending their meager funds on luxuries, the report points out.

“Is using more than one roll of toilet paper a week really a luxury (especially during periods of intestinal distress)?” the study asks. “Or what if you have a chronic medical condition that requires ongoing use of over-the-counter remedies (e.g., antacid tablets, vitamins, hemorrhoid ointment, antihistamine, or eye drops)? All of these items are typically only available in the commissary, and only for those who can afford to pay.”

Prices for regular commissary goods are generally comparable to prices found in stores, however, according to the report. PPI suggests that while private commissary vendors benefit financially from monopoly contracts with prisons, and lower operating costs than businesses that sell goods to the “free world,” commissary prices often do not reflect the savings.

Price gouging is apparent in the exorbitant prices for digital services like music streaming and messaging services offered to inmates, researchers found. “Prisons and jail telecommunications providers are aggressively pushing these new products and services, where they can charge prices far higher than similar businesses do outside of the prison setting,” the report states.

Through charging inmates for basic necessities, prison systems can levy a portion of the financial burden of incarceration back onto incarcerated people and their families. Instead, the report suggests states looking to save money on prisons should do so by cutting prison populations.

And little-studied prison commissaries should be the subject of evaluation by law- and policymakers.

“Prisons are unusual retail settings, data are hard to find, and it’s hard to say how commissaries “should” ideally operate,” the report says. “As the prison retail landscape expands to include digital services like messaging and games, it becomes even more difficult and more important for policymakers and advocates to evaluate the pricing, offerings, and management of prison commissary systems.”