Twenty-five years ago, the massive Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which, among other things, prevented incarcerated students hoping for a college degree from accessing Pell Grants, was signed into law by then-President Bill Clinton, and essentially resulted in the slashing of opportunities for higher education in federal and state prisons across the U.S., a move that, as Mikaol T. Nietzel, president emeritus of Missouri State University, wrote for Forbes recently was “a foolish decision, driven by political posturing rather than financial necessity or sound policy.”

And so it has been for a quarter-century.

In April of this year, however, the Restoring Education and Learning Act—or REAL Act—was introduced into the U.S. Senate by Senators Brian Schatz (D-HI), Mike Lee (R-UT), and Dick Durbin (D-IL), with companion legislation introduced in the House of Representatives by Reps. Danny Davis (D-IL), Jim Banks (R-IN), Barbara Lee (D-CA), and French Hill (R-AK).

If passed, the REAL Act would reverse the 1994 Pell grant ban, thus finally unlocking financial aid for men and women in the nation’s prisons. The legislation’s early supporters include such organizations as the American Bar Association, the American Council on Education, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, the American Correctional Association, the Equal Justice Initiative, the ACLU, and more.

The ABA noted in its letter of support for the bill that, in 2013, the RAND Corporation performed a deep analysis of data from multiple studies, and emerged with the firm conclusion that “correctional education programs decrease recidivism and increase ex-offender employability.”

Fred Patrick, the Director of the Vera Institute of Justice Center on Sentencing and Correction, wrote a smart and very informed essay on the importance of the REAL Act—-which is still in the early stages of the legislative process, yet has recently seen its already cheeringly bipartisan support picking up new steam.

We should also mention here that, shortly before the 4th of July, the widely-liked and highly respected Patrick passed away, leaving colleagues and friends at the Vera Institute and elsewhere grieving. Patrick’s passing also makes this last essay on a subject to which he devoted so much of his time seem all the more urgent.

Patrick’s essay, which you’ll find below, is especially powerful when combined with Vera’s excellent May 2019 report on the same topic, “Unlocking Potential: Pathways from Prison to Postsecondary Education,” which is co-authored by Patrick, Ruth Delaney, and Alex Boldin.

Now over to Fred Patrick.

Bringing Dignity & Promise to Life Behind Bars & After Through Higher Education

by Fred Patrick

The Vera Institute of Justice has long been and will remain committed to removing all barriers to high-quality postsecondary education in prison because of its transformative benefits, including the power to break the cycle of mass incarceration and poverty.

Since 2016, Vera has provided technical assistance to colleges participating in the U.S. Department of Education’s Second Chance Pell Experimental Sites Initiative, a groundbreaking initiative with many of the student success-centered elements of a program we launched in 2012 called “Unlocking Potential: Pathways from Prison to Postsecondary Education” that supported three states’ operations of college programs in their prisons. (You can read more about Pathways in a new report we released last month.)

Together these programs, and others like them, have helped to dramatically change the landscape of accredited, higher education programs operating in the U.S. But far too many people who are eligible to enroll in postsecondary programming cannot, due to state and federal barriers that effectively bar anyone in prison from receiving tuition assistance.

We now stand at a pivotal moment where that could change. Members of Congress from both sides of the aisle are rallying around the repeal of the ban on Pell grants for people in prison as the next logical step in criminal justice reform, thanks to the tireless efforts of a broad array of advocates from across the political spectrum, including justice-involved people (many of whom participated in college in prison programs), corrections professionals, higher education faculty and administrators, and nonprofit organizations committed to reentry, social justice and criminal justice reform.

People who participate in postsecondary education in prison are at least 48% less likely to recidivate than their peers who don’t

Vera believes advocates and organizations engaged in the fight to reform our criminal justice system should leverage this unique moment by making the commitment to push for a policy change that impacts the most people possible. Reinstating Pell grants for people in prison without eligibility restrictions is the best way to do that, which is why it should be a priority now and why it must remain a priority for however long is necessary to get the job done. Here are three reasons why:

Postsecondary education in prison increases economic opportunity for justice-involved people. Our research estimates that lifting the ban on Pell grants would increase employment rates among formerly incarcerated students by an average of 10 percent, resulting in an increase in combined earnings among all formerly incarcerated people by $45.3 million during the first year of release alone. Furthermore, equipping justice-involved people with new knowledge and skills provides employers with a larger pool of skilled workers to hire.

Postsecondary education in prison creates safer prisons and communities. Education adds humanity to the prison experience and fosters an environment of hope, rather than one of despair and fear that can often lead to violence. More than 90 percent of people in prison will eventually be released. Still, about a third of people who are released from prison re-offend within just three years. Barriers to postsecondary education contribute to high recidivism rates because 64 percent of all new jobs require some form of it, but the vast majority of people in prison don’t have postsecondary credits on their resume, which makes securing a job an obstacle that’s all the more difficult to overcome. This helps to explain why people who participate in postsecondary education in prison are at least 48 percent less likely to recidivate than their peers who don’t. Their ability to secure jobs and other opportunities upon release allows them to become contributing members of their community, which increases public safety.

Corrections professionals and prison populations at large benefit when educational programming is more accessible, too. In many cases, individuals serving life sentences are seen as advisors and help set the example for others in prison to follow. When those mentor figures participate in educational programs, others want to follow in their footsteps. Allowing the broadest group of people to participate in postsecondary courses provides the greatest benefits to the greatest number of people, including those living and working in prisons and those in the communities offenders will return home to.

Breaking the recidivism cycle

Postsecondary education in prison cuts costs, which provides opportunities to reinvest in communities. “Safer communities” is another way of saying less crime and fewer taxpayer dollars spent on prisons. According to the findings of Vera’s 2015 “Price of Prisons” report, states spend upward of $45 billion a year incarcerating people but continue to see little return on that investment. Expanding access to postsecondary education in prison, on the other hand, has a solid track record of cutting costs. A recent report we co-authored with the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality found reduced recidivism rates would save states a combined $365.8 million in decreased prison costs per year.

At a time when an increasing number of states are implementing sentencing reforms that are leading to more and more people who were serving extended or life sentences being released, expanding access to postsecondary education in prison by reinstating Pell grants without eligibility restrictions is also a forward-thinking move that would remove barriers that could undermine sentencing reform.

It’s our hope that others will support maximizing the potential for each of these benefits by supporting the repeal of the Pell ban without eligibility restrictions through the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act or passage of the REAL Act.

Fred Patrick joined the Vera Institute of Justice in July 2012 as the project director of the Pathways from Prison to Postsecondary Education Project. In 2015, he was named director of the Center on Sentencing and Corrections, which he led until his passing in July 2019. As director of CSC, Fred led his team to envision a commitment to human dignity even in prison, including work to expand access to college in prison and eliminate solitary confinement, reduce the use of jails, and increase access to public housing for people coming home from prison. “Fred pursued a life of public service and generosity,” wrote his colleagues at Vera. “There are thousands of people throughout the country who are thriving today because of Fred’s work.”

This essay by Fred Patrick was first published in Think Justice Blog, produced by The Vera Institute of Justice, and is republished with their kind permission.

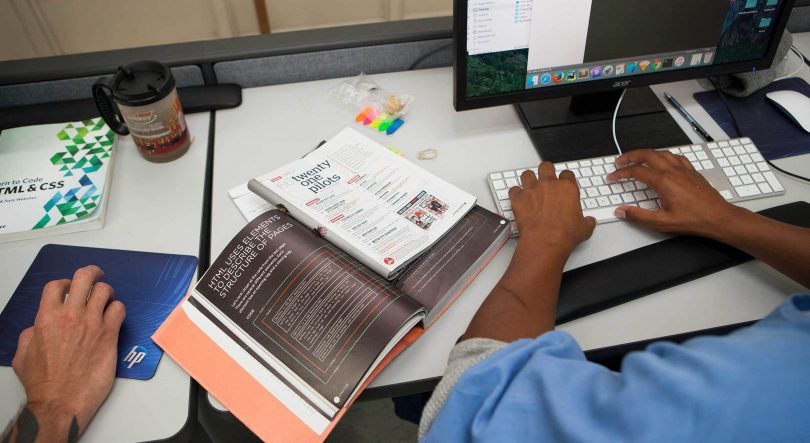

The photo at the top of the story is courtesy of the California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation.

False economy to not allow pell grants to people who are incarcerated. The U.S. has the highest recidivism rate in the world! It is proven that education, rehab, and life/job skills training programs all reduce very expensive recidivism.

Nonsense. Hardcore criminals are hardcore criminals by choice. They are tigers who do not change their stripes. Go ahead and educate them, and the only result will be smart ass defendants who want to represent themselves after they parole and immediately re-offend.

Dream on libs…

[…] “Momentum grows in Congress to expand high quality post-secondary education in prison,” Witness LA […]