Incarcerating individuals for drug-related offenses does not lead to reduced drug use or fewer overdoses, according to a newly released report from Pew Charitable Trusts, which the non-profit sent last summer to President Donald Trump’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis.

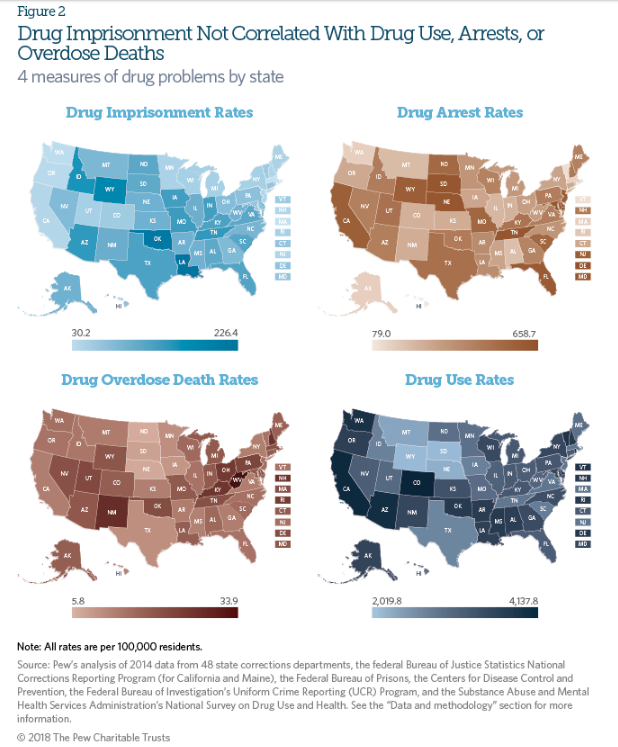

The report, which looked at federal and state law enforcement, corrections, and health agency data from 2014 looking for patterns that may inform efforts to combat the nation’s opioid crisis, found that there was no “statistically significant relationship” between states’ incarceration rates for drug crimes and three specific factors that can reveal a state’s got drug problems: drug arrests, drug overdose deaths, and self-reported drug use (excluding marijuana).

There are approximately 300,000 people in state and federal lockups for drug crimes. In 1980, there were only 25,000 people serving state or federal prison sentences for drugs. Since that time, the average length of drug-related prison stays has increased significantly, thanks in large part to the laws and policies put in place during the “tough-on-crime” era, which was partly a reaction to the rise of crack cocaine, and focused on harsh punishment as a deterrent.

Yet, between 1990 and 2014, self-reported drug use—and the availability of heroin, cocaine, and meth—increased nationally. In 2015, more than 33,000 people fatally overdosed on opioids, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And heroin overdoses increased 20 percent from 2014 to 2015.

But states have had significantly varied law and policy responses to the opioid crisis, and thus, have different rates of drug imprisonment.

Louisiana, for example, had the highest rate of imprisonment for drug offenses of any state in 2014, at 226.4 per 100,000 residents–a rate that was more than twice as high as 37 other states. (The only states that had larger drug offender populations were California, Florida, Illinois, and Texas, which have much larger populations overall.) Oklahoma took second place with 213.7 drug incarcerations per 100,000 residents. In comparison, Massachusetts, which had the lowest rate of drug imprisonment, locked up 30.2 people out of every 100,000.

If the tough-on-crime focus on deterrence had been successful, then states that sent more people to prison for drug crimes would—all other things equal—also have lower rates of drug use, the Pew report says.

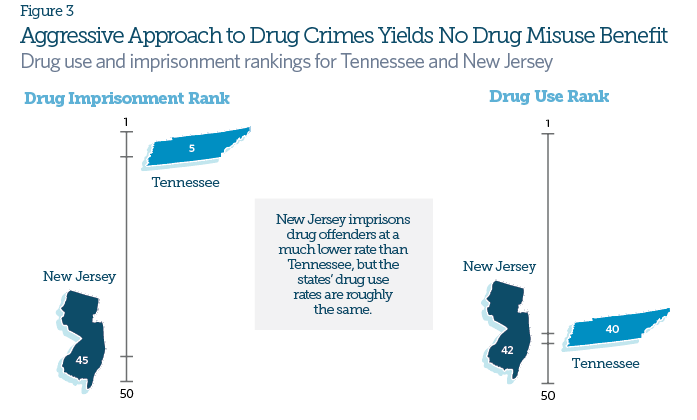

This is not the case, however, according to the report. While Tennessee had a much higher rate of drug imprisonment than New Jersey in 2014, the two states had similar rates of drug use.

California, which ranked second after Colorado for the highest rate of adult illicit drug use in 2014 and had the eighth highest drug arrest rate, had the fourth lowest rate of drug imprisonment of all the states. (Note: since the November 2014 passage of Proposition 47—which reduced six drug and property felonies to misdemeanors—California’s numbers have likely changed quite a bit.)

While Louisiana and Oklahoma ranked first and second for the highest rate of drug imprisonment, they ranked thirteenth and tenth respectively for adult illicit drug use. Wyoming, the state with the third-highest rate of drug-related incarceration, had the lowest rate of illicit drug use among residents, according to the state and federal data analyzed in the report.

And Pew’s results hold up, even when the nonprofit controlled for variables like the percentage of college-educated residents, states’ unemployment rates, median household income, and the percentage of the population that was nonwhite.

“The evidence strongly suggests that policymakers should pursue alternative strategies that research shows work better and cost less,” researchers wrote.

Pew also conducted polls in four states—Louisiana, Oklahoma, Utah, and Maryland—all of which came back showing widespread, bipartisan support for reducing drug incarceration and using savings to boost funding for alternatives to incarceration.

In Oklahoma, 84 percent of those polled said they supported shorter sentences for nonviolent offenses and larger investment in substance abuse and mental health services, as well as probation and parole.

Sixty-three percent of Louisiana’s respondents (including 54 percent of Republicans, 66 percent of independents, and 69 percent of Democrats) approved reducing sentences for low-level drug offenses while maintaining long sentences for more serious drug dealers.

“Although no amount of policy analysis can resolve disagreements about how much punishment drug offenses deserve, research does make clear that some strategies for reducing drug use and crime are more effective than others and that imprisonment ranks near the bottom of that list,” the Pew report concludes. “Putting more drug-law violators behind bars for longer periods of time has generated enormous costs for taxpayers, but it has not yielded a convincing public safety return on those investments. Instead, more imprisonment for drug offenders has meant limited funds are siphoned away from programs, practices, and policies that have been proved to reduce drug use and crime.”

No shit Sherlock…ohh that’s right this is a conservative site that quietly endorses the LA sheriff department

Taking a wild guess that this is the first time WLA has been called a conservative site

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Hi, Jim,

Um, yeah. This is definitely a first. 🙂

C.

“No shit Sherlock” an out of date saying most likely uttered by a middle aged white guy trying to be funny. Cf-2 uses it all the time, looks like he’s trying a new persona.

In “plain speak” you’re basically stating that an “Old White Man” is caught in a time warp attempting some humor. LMAO!

I’m visualizing the character “Biff” in “Back to the Future” I love it when new commenters/characters come up with gobbledygook on this site.