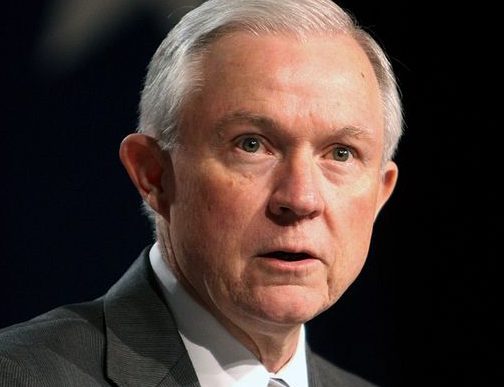

On Tuesday, the U.S. House of Representatives slapped Attorney General Jeff Sessions on the issue of civil asset forfeiture with three amendments to an important appropriations bill, each of which prohibits the Department of Justice from using funds to increase certain federal and local forfeiture practices.

In July, Sessions announced his intention to roll back the limitations placed on the practice by the Obama administration, and, in general, to strengthen the federal government’s power to seize cash and property from Americans without having to first bring criminal charges against them.

One amendment passed by the house would block the DOJ from funding any of the activities that were prohibited by a 2015 directive from former attorney general Eric Holder limiting the program. This amendment was sponsored by a bipartisan group of nine House members led by Republican Justin Amash of Michigan, plus Democrats Ro Khanna of-California, Pramila Jayapal, of Washington state, and Hawaii’s Tulsi Gabbard, and more.

“It is an unconstitutional practice that is used to violate the due process rights of innocent people,” a furious Amash all but shouted from the house floor, in reference to the civil asset forfeiture issue.

Tulsi Gabbard was equally emphatic. “Forfeiture efforts tend to target poor neighborhoods,” she said, adding that forfeiture “does not discriminate between the innocent and the guilty.” Asset forfeiture is “a crime against the American people committed by their own government.”

Two other amendments, one from Michigan Republican Tim Walberg, and a third from Maryland Democrat Jamie Raskin, would ban the Justice Department from using funds to enforce Sessions’ new July orders.

And another related amendment from California Republican Rep. Darrell Issa would use funds gained from asset forfeiture to reducing the backlog of rape kits.

WitnessLA has reported frequently on civil asset forfeiture laws, which allow government entities to keep money, cars, real estate, and other property that may be associated with a crime (usually a drug crime). Law enforcement agencies in California and other states circumvent their own states’ forfeiture laws through the controversial federal Equitable Sharing Program, which authorizes law enforcement agencies to use seized money as revenue, with only “probable cause” that laws have been broken, by bringing the feds into an investigation. Civil forfeiture has existed in some form since the colonial era. The modern practice dates primarily since the 1980s when the war on drugs was in high gear.

Now, asset forfeiture has become a lucrative tactic for law-enforcement agencies to pump up their cash flow in an era of tight budgets.

A Justice Department inspector general’s report released in April found that federal forfeiture programs had taken in almost $28 billion over the past decade, and the Washington Post reported that, in 2015, civil-forfeiture seizures nationwide surpassed the collective losses from all burglaries that same year.

Across the nation, local agencies are using the tool as a cash cow, taking money and property from people who have not been convicted of a crime.

Yet, despite the inspector general’s report, Sessions was not persuaded that there was anything wrong with the practice. “President Trump has directed this Department of Justice to reduce crime in this country, and we will use every lawful tool that we have to do that,” he said at a gathering of law-enforcement officials after his July directive. “We will continue to encourage civil-asset forfeiture whenever appropriate in order to hit organized crime in the wallet.”

This week’s house amendments must also be passed by the Senate, and then the appropriations bill itself must be passed. If approved by both houses, finally both bill and amendments will head for Donald Trump’s desk for a signature. And, even if passed and signed, the amendments won’t completely solve the asset forfeiture problem.

Yet, they send a strong signal.

Street Vender’s Cash Forfeiture

As luck would have it, the house’s action came just days after a video went viral of a UC Berkeley campus police officer taking $60 in cash out of a street vendor’s wallet, after citing the hot dog vendor for not having the necessary permit to sell his wares. A Berkeley alum named Martin Flores happened to be buying a hot dog from the vendor, and captured the money grabbing scene on his phone, then uploaded it to Facebook, where it was quickly shared on other social media platforms and viewed more than 11 million times.

UCPD spokeswoman Sgt. Sabrina Reich told local publication Berkeleyside that the $60 was “seized as suspected proceeds of the violation and booked into evidence.” Reich also said three other people were detained on suspicion of vending without a license, but they were released with a warning. The UCPD added to another reporter that police have a right to seize cash from anyone subject to an arrest or citation.

Whatever the upshot and meaning of the hot dog vender’s experience, lawmakers in DC and in California have begun to take action to contain the practice.

In 2016, California Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill to prevent agencies from profiting from cash and property taken from civilians who have not been convicted of a crime.

The ACLU and other reform advocates joined in support of the House amendments, which they viewed as an important step.

“Our organizations believe that the ‘civil forfeiture system undermines property rights and is fundamentally unjust,’” wrote Kanya Bennett, ACLU legislative counsel. “The ACLU is particularly concerned with civil forfeitures’ impact on poor people and people of color.”

Even his own party of Republicans knows that Sessions is a Jim Crow throwback and a dingbat.

there is at least one good reason to allow for a temporary rollback of AG Holder’s 2015 directive curtailing the exercise of civil-asset forfeitures.

Loosening the current restrictions on forfeiture, accompanied by the collection of statistical data on crime, could provide an informative comparison revealing the actual effect and effectiveness of this controversial law enforcement tool.

Because, on its face, the federal program for participation in civil asset forfeiture with local law enforcement creates a financial incentive to partner, promote, protect and perpetuate revenue producing criminal activities, like illicit drug commerce, within their zone of jurisdiction.

By allowing Sessions to go forward, we could find out – for example, did the volume of illicit drug sales decrease after local law enforcement became unrestrained to practice civil asset forfeitures?

Or was there a measurable increase?

What about the frequency of other crimes which are often associated with the sales and use of illicit drugs, did those decrease or increase?

A multitude of factors influence how a local law enforcement agency deploys its resources and determines operating policies.

How will that mix be altered when law enforcement can use an administrative mechanism to share in revenue generated by illicit drug commerce?

Does it help decrease crime,

or does crime follow the prediction of our model =

increase?

Good call.

Ironic how after the election Trump’s boys came out like a category 5 hurricane then fizzled to a tropical storm. If they deviate one bit, they’re humiliated and/or pressured to resign in lieu of being publicly fired. The circus continues.