Editor’s Note:

This essay, by Adnan Khan is the second in what we hope will be a series of essays written through the FirstWatch project at San Quentin State Prison. With their writing, the journalists, who are also San Quentin inmates, aim to, as they put it, to explore “the connections, challenges, and intimacies between self, society, and incarceration.” With Tuesday’s election in mind, in this essay, author Kahn took an intriguing and unusual intellectual journey through the meaning of voting, and the complicated effects of having that right taken away. Happy reading!

(Go here to read San Quentin author James King’s essay, also on voting, which ran earlier on Monday.)

And be sure to vote!

Elections: For Members Only

By Adnan Khan #F-55145

Soon, my friends from the San Quentin Newspaper will be doing a “mock election” on the yard. Guys on the main line as well as the men on condemned row will be able to “go to the polls” and vote. I know there to be liberal and conservative men here in San Quentin who have compelling political interests. I look forward to participating in this interesting experiment and I’m excited to see what the results this mock election will reveal.

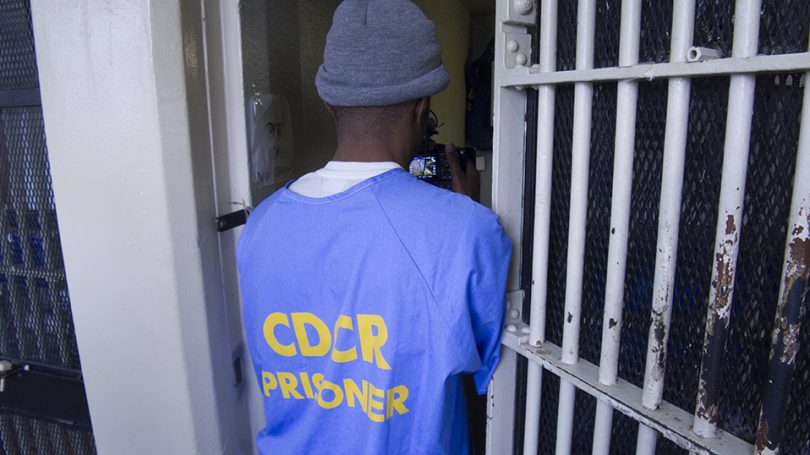

But that’s as far as an incarcerated person’s voting contribution can go; a private, mock election inside of prison walls. Incarcerated people in prison cannot vote in California. Voting is a right for obedient citizens and since we’ve forfeited that right by committing crimes, our citizenship as Californians, as Americans (maybe even as humans) has been revoked.

An interesting thought comes up for me when I think about my right, or lack of right, to vote. I question my membership in society, what that looks like or does not look like. I’m not actually sure. Am I a member of society? If so, where is my place in a constituency? If not, then simply, why not? Why can I not vote? Further, I wonder what psychology the public functions from; their implicit biases towards incarcerated humans, to accept the logic that voting for us does not matter.

In Discipline and Punish, Michel Foucault speaks about the public’s psychology in reference to an incarcerated person’s membership. He describes a citizen’s thought process.

Foucault argues that by committing a crime, we have violated the social contract of society, and individually, attacked people’s social rights. Therefore, society has the absolute right to oppose us in totality. As a result, the pendulum of due process swings to one side where all the rights, resources, and power are dominated by everyone but the responsible party. It is believed that by attacking the society’s rights, we ceased to be a member of it, because the preservation of “state” and “country” has been unpredictable for us. Therefore, as incarcerated people, we become a common enemy, actually worse than an enemy; he or she becomes a traitor. An enemy is respected. The lines of hostility are clearly drawn, an expectation of harm is transparent. A traitor is worse; the unexpected assault comes from right within society. And so, a crime is committed, and when we punish the guilty, we punish not so much a citizen, we punish a traitor.

Traitors should not have the right to vote nor have any say so in how society functions. Reducing a person’s identity to “traitor” is dehumanizing. It then makes it morally accessible to treat someone with marginalization and strip them of their rights. Perhaps the punishment of banishment and removal of membership is correct. However, upon my release, I am going to a society in which I am expected to participate. I am required (and I require myself) to be a law abiding citizen. My citizenship is a condition of parole. Therefore, I actually am a member of society, not an enemy, especially not a traitor. And so, as a currently incarcerated member of society, for me to participate in the structuring of the community I’ll be living in, contributing to, and providing service for, is important.

When I approach the ballot box on the Lower Yard, I will not be thinking strictly about myself. I’ll be thinking about the pot holes my sister has to drive over. I will have in mind my niece and nephew’s education. I’ll be considering my grandmother’s well being. Problems with infrastructure, school superintendents and allocation of resources, and affordable healthcare are all important to me, incarcerated or not. As a member of my family, I want what’s best for my family. As a member of society, I want what’s best for society. I believe my voice matters in both.

Author Adnan Khan is the Co-Founder of Re:store Justice and FirstWatch, a media project created and produced entirely by a group of journalists incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison. Khan shares his worldview through storytelling, with the hopes of using his platform to mentor youth and provide success opportunities for neglected children.

Additionally, Khan works in collaboration with survivors of crime, incarcerated men, district attorneys, CDCR officials and other stakeholders to move towards healing and integrating communities. He is currently serving a 25-to-life sentence and has been incarcerated over for 15 years.

Re:vision, where this essay was first published, is a series of personal blogs written through the FirstWatch project at San Quentin State Prison. Through traditional postal mail letters, the journalists delve into a list of topics, looking at them through a lens that includes the complex interweave of relationships between self, society, and incarceration, also opening themselves up to responding to perceptions and questions posed by the public.

FirstWatch is a media project started by a group of men incarcerated at San Quentin, in collaboration with Re:store Justice, which works in partnership with incarcerated people, survivors of crime, district attorneys, and the community. Their mission is to re-imagine and reform our criminal justice system to be one of true inclusion and justice.