by Robert Lewis

Reacting to a CalMatters investigation, state lawmakers said they’re concerned about defendants’ long waits behind bars before trials and substantial backlogs in California’s courts. And they’re touting their bills as steps toward fixing the problem.

Included are proposed laws that would release defendants with zero bail, limit fees on bail bonds and eliminate peremptory challenges that can slow down jury selection, among other measures.

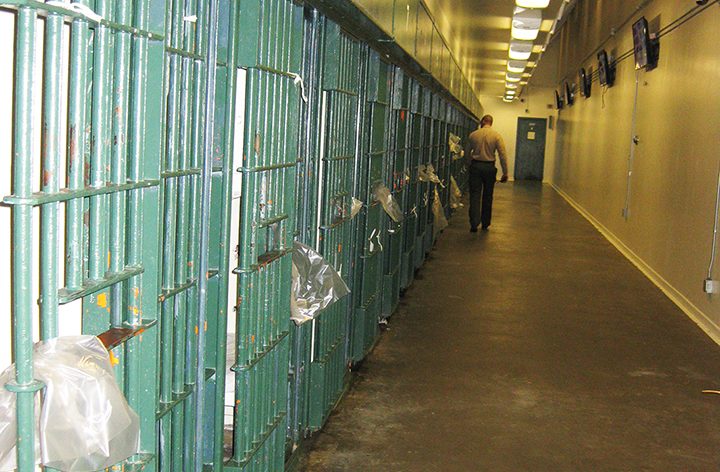

At least 1,300 unsentenced criminal defendants have been locked in county jails for longer than three years, including about 330 people incarcerated for longer than five years, according to the CalMatters report Waiting for Justice. The majority are Black or Latino.

In one Fresno County case, a man accused of murder has been held in jail for nearly 12 years without going to trial. The long waits for justice take a toll on defendants — and the victims of crimes.

State Sen. Tom Umberg, a Democrat from Santa Ana, and chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, called CalMatters’ findings “surprising and embarrassing.”

“I am very concerned about the backlog in the courts. I’m very concerned about justice being delayed, maybe justice being denied,” he said.

Support for the proposals among legislators, however, is unclear. Some of these issues have come up frequently in the past, so it remains to be seen how much the bills will change since they are still early in the legislative process.

Revisions to cash bail, in particular, have been messy in California in recent years. Voters last year rejected Prop. 25, which would have ended cash bail, by a vote of 56% to 44%.

“I’m very concerned about justice being delayed, maybe justice being denied.”

State Sen. Tom Umberg (D-Santa Ana)

California’s criminal courts have struggled to dispose of cases in a timely manner — even before the pandemic — for myriad reasons, including defense attorneys seeking extra time to prepare cases, prosecutors pursuing stiff sentences that lead to extra hearings and judges failing to manage their crowded calendars.

Some influential Democrats said CalMatters’ findings provide more proof of the need for changes in the bail system, an issue progressive lawmakers have been championing for several years.

“A lot of people…are held in jail just because they’ve got no money, not because they’re a flight risk or a public safety risk,” said state Sen. Robert Hertzberg, a Los Angeles Democrat who also sits on the judiciary committee.

The California Supreme Court recently ruled that defendants can’t be held in jail solely because they can’t afford to make bail. However, the ruling leaves a number of questions unanswered.

“They didn’t tell us how to solve the problem. They just said that here is the problem,” said Hertzberg, who is co-sponsor of a bill that would set bail at zero dollars for most nonviolent crimes. “There’s still more that needs to be done.”

Assemblymember Reginald Jones-Sawyer, a South Los Angeles Democrat and chair of the Public Safety Committee, is also pushing for more bail reform.

“We’ve created a system which imprisons people of color into this prison industrial system,” said Jones-Sawyer, who’s sponsoring a bill that would eliminate some bail fees. “If you can’t pay bail, you’re stuck in jail for a long period of time. And we pay that cost. Taxpayers pay that cost.”

Courts can’t handle volume

Jones-Sawyer said the inequities in the system, including lengthy pretrial detention, aren’t surprising to poor people or many Black and Latino residents. The key now is that “we don’t close our eyes again and go back to sleep and not take care of it.”

Assemblymember Kevin Kiley, a Republican from Rocklin and a member of the Judiciary Committee, said the issue isn’t necessarily bail — it’s that the courts can’t handle the volume of cases.

“The inadequate capacity of our justice system has been well understood for some time. And it’s not just in criminal cases, by the way, and it’s not just the trial court level…You have cases that are civil, before the court of appeals, that are waiting years for a hearing,” Kiley said.

“What we need to do is have a criminal justice system and overall justice system that is designed to produce fair outcomes in a timely manner.”

But reforming the courts to pick up the pace is difficult because of their independent function.

“I don’t think there’s much the legislature can do to force them to move cases more quickly,” said Natasha Minsker, a Sacramento attorney and consultant on criminal justice issues. It’s why disparate criminal justice reform bills might be the best hope of tackling elements of the backlog.

She said efforts to get more low-level defendants into diversion programs and to limit the use of sentencing enhancements might also help.

“I do think ultimately sentencing reform is part of the solution,” Minsker said.

So too is money, some lawmakers said.

California’s criminal courts have struggled to dispose of cases in a timely manner — even before the pandemic — for myriad reasons, including defense attorneys seeking extra time to prepare cases, prosecutors pursuing stiff sentences that lead to extra hearings and judges failing to manage their crowded calendars.

Some influential Democrats said CalMatters’ findings provide more proof of the need for changes in the bail system, an issue progressive lawmakers have been championing for several years.

“A lot of people…are held in jail just because they’ve got no money, not because they’re a flight risk or a public safety risk,” said state Sen. Robert Hertzberg, a Los Angeles Democrat who also sits on the judiciary committee.

Assemblymember Kevin Kiley, a Republican from Rocklin and a member of the Judiciary Committee, said the issue isn’t necessarily bail — it’s that the courts can’t handle the volume of cases.

“The inadequate capacity of our justice system has been well understood for some time. And it’s not just in criminal cases, by the way, and it’s not just the trial court level…You have cases that are civil, before the court of appeals, that are waiting years for a hearing,” Kiley said.

“What we need to do is have a criminal justice system and overall justice system that is designed to produce fair outcomes in a timely manner.”

But reforming the courts to pick up the pace is difficult because of their independent function.

“I don’t think there’s much the legislature can do to force them to move cases more quickly,” said Natasha Minsker, a Sacramento attorney and consultant on criminal justice issues. It’s why disparate criminal justice reform bills might be the best hope of tackling elements of the backlog.

She said efforts to get more low-level defendants into diversion programs and to limit the use of sentencing enhancements might also help.

“I do think ultimately sentencing reform is part of the solution,” Minsker said.

So too is money, some lawmakers said.

“The courts are a separate, independent branch of government and, understandably, they want to be responsible — and they should be responsible — for their own administration. Our primary function with respect to the courts is a resource function,” said Umberg, who is a former federal prosecutor.

The reality is our courts are under-resourced and people are suffering because of it.

State Assemblymember Ash Kalra (D-San Jose)

Courts for years have submitted reports to the Legislature showing a need for more judges to handle the workload.

“The reality is our courts are under-resourced and people are suffering because of it,” said Assemblymember Ash Kalra, a San Jose Democrat and member of the Judiciary Committee. More resources for overloaded public defenders would also help the problem, he added.

Last year’s budget cut $200 million in state general fund money for the judicial branch.

At a joint hearing of the Senate and Assembly judiciary committees in late February, lawmakers grilled judicial branch officials for more information on the size of the backlog and what’s needed to clear it.

“I know you want full restoration. That’s been an ongoing subject. However, there are a lot of questions that need to be addressed so that we can ensure that the levels of access to justice in every single county is available,” said Assemblymember Mark Stone, a Monterey Bay Democrat and chair of the Judiciary Committee.

CalMatters’ investigation revealed that the state doesn’t actually know how bad its backlogs are and how long cases are taking to resolve. Many courts are incapable of providing accurate data.

Courts want funding restored

For its part, judicial branch leaders are hopeful they will get funding restored in the current budget proposal. But they say the courts need more than money to clear the backlog.

The Judicial Council, which is the judiciary’s policymaking body, is using the budget process to push for an expansion of an early disposition program to speed up some lower-level criminal cases. The theory is by getting rid of large numbers of cases quickly, the courts will have more resources to handle the more time-consuming felonies and civil proceedings.

The council also is working on a proposed budget trailer bill that would allow the courts to continue holding some civil proceedings remotely even after the pandemic ends. Court leadership was able to authorize such time-saving technology with emergency orders, but it will need a legislative fix to make it permanent.A council advisory committee is soliciting comments on a similar proposal to sponsor legislation allowing remote appearances in criminal proceedings.

“The courts have pretty limited options when it comes to making significant changes to court procedure,” said Cory Jasperson, the Judicial Council’s director of government affairs. Much of it is set by statute and needs to be changed by lawmakers, he added.

Kello Gordon looks at a photo of her son, David Lee Williams, in her Sacramento home. Arrested in 2019 for allegedly stealing a car and illegally possessing a firearm and drugs, Williams cannot afford bail to get out of Sacramento County jail so he’s been held for two years while he awaits his trial. Photo by Anne Wernikoff, CalMatters

CalMatters found that lawmakers have rejected a number of changes the judicial branch backed in recent years that purportedly would have made court operations more efficient.That includes measures to allow non-judges to handle some proceedings, limit the types of cases where court reporters are necessary and speed up jury selection in some cases.

It’s unclear how much support the judicial branch’s proposals have. Labor groups have been among the critics of increasing the use of remote proceedings.

Jones-Sawyer, the Assembly’s public safety chair, is hopeful.

The emergency changes made during the pandemic including the use of remote hearing technology “shed some light on ways we could do things better and giving people an opportunity to not have to come down to court,” he said. “We have to work in partnership with the judicial branch.”

Author Robert Lewis covers justice issues. Before joining CalMatters he worked at print and public radio outlets across the country including WNYC-New York Public Radio, Newsday and The Sacramento Bee. His investigative reporting has garnered some of the industry’s highest honors including a George Polk Award, an Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award and Sigma Delta Chi Awards.

This article first appeared on CalMatters Network and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.