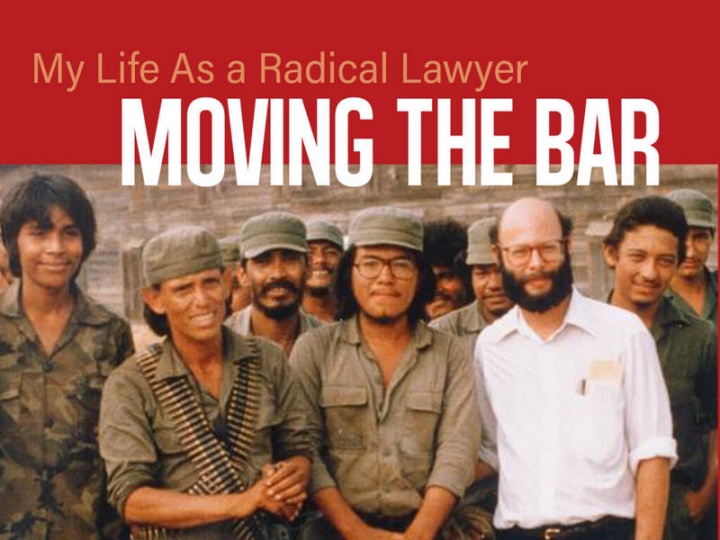

MOVING THE BAR: MY LIFE AS A RADICAL LAWYER

by Michael Ratner

OR Books, New York/London 2021, 358 pages

Reviewed by Stephen Rohde

I miss Michael Ratner. We all should.

I met Michael when we were both students at Columbia Law School in the late 60’s. He was smart and funny. I joined the student chapter of the National Lawyers Guild that he had helped establish. It was described in the yearbook as dedicated to the proposition that “America’s law schools and legal system should, for the first time, begin to respond to the needs of the masses of American people, and not the wishes of the Rep-Dem Party, the Mafia, and General Motors, its subsidiaries, and apologists.” Members of the student chapter sought to use the law “to eliminate militarism, imperialist wars, the growth of a police state, and to eradicate racism.” Michael designed his whole life with those goals in mind, and he was living up to his goals, achieving enormous success, until cancer stole him from us all too soon in May of 2016.

Columbia’s yearbook itself tells a lot about how transformative those years were. Inside the front cover is a photograph of Wall Street. Inside the back cover is a photograph of ten NYPD patrol cars guarding the law school building. We had entered law school in 1966, aspiring to take our places, if not all on Wall Street, in positions of stature as prominent and successful members of the American legal profession. But by the time we left in 1969, many of us had become active in resisting US aggression in Viet Nam and opposing racism, all of which came to a head in 1968, as students occupied university buildings demanding that Columbia cancel its contracts with federal agencies involved in the war and halt the building of a gymnasium in Harlem’s Morningside Heights, which was designed with one entrance for Columbia students and the other for predominately Black residents from the community.

Neither Michael nor I joined in the occupation, but we both participated in the campus protests. One night at about 2 a.m., as he vividly writes in his compelling and irresistible new autobiography, Moving the Bar: My Life as a Radical Lawyer, Michael linked arms with fellow protestors on the steps of the iconic Low Library. Suddenly appeared “waves of cops flooding through the main gates, more than a thousand of them, some in uniform, some in plain clothes . . . As the police marched toward us in military formation, we tightened our chain of arms and began to sing ‘We Shall Overcome.’ But it was over in seconds. Armed with billy clubs, the cops stormed our puny barrier and started swinging. A muscular cop in plain clothes picked me up like a matchstick, carried me a few feet, threw me on the ground, and gave me a couple of hard whacks with his stick. I lay stunned.”

That night, 150 injured students ended up in the hospital; more than 700 were arrested and taken into custody. But the brutal police violence backfired. Students led a massive strike that effectively shut down Columbia for the rest of the year. The university president resigned, Columbia canceled most of its work with the Pentagon, and it abandoned the proposed gymnasium. The Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR) filed a federal lawsuit against the university.

The entire experience radicalized Michael. For him, the “extraordinary political-legal lawsuit” that CCR filed against Columbia “changed the way I viewed the law.” The lawsuit combined legal claims with “political points about Columbia’s wrongs and its authoritarian structures.” One of the main purposes of the lawsuit was to publicize students’ demands and legitimate the sit-in. The lawyers understood that “their clients’ political struggle must remain front and center.” Although the lawsuit did not succeed in court, it would transform how Michael understood and practiced law throughout his career. Years later he would become Legal Director and President of CCR.

As Michael’s close friend and radio co-host Michael Steven Smith writes in his warm and loving Foreword, “Michael will be remembered as a generous, loyal friend and a gentle and kind person. He was a compelling speaker, an acute observer of the political scene, and a farsighted visionary. Professionally, Michael will live on as one of the great advocates for justice of his time.”

Michael was in the midst of writing his autobiography when he died in 2016. His family asked friend and a writer, to complete the book based on Michael’s notes and articles, previous interviews, and the recollections of friends and family.

Moving the Bar: My Life as a Radical Lawyer is an honest, poignant, sprawling, remarkable, and inspiring account of how a middle-class Jewish kid from Cleveland chose not to go into the family building-supply business but instead became a visionary and peripatetic human rights lawyer, advancing the cause of justice through litigation and political organizing not only in the United States, but in Cuba, Nicaragua, Grenada, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, and Costa Rica, and Mexico.

Michael was in the midst of writing his autobiography when he died in 2016. His family asked Zachary Sklar, a friend and a writer, to complete the book based on Michael’s notes and articles, previous interviews, and the recollections of friends and family. Sklar does an admirable job. The book reflects Michael’s spirit, candor, and insight to the very end.

Michael attended Brandeis University but took a year off during which he stayed mostly to himself in a dumpy apartment in Cambridge reading Theodore Dreiser, Lawrence Durrell, Ernest Hemingway, and much more. His father had died and it was “the worst time of my life.” The war in Vietnam was escalating. Since he was no longer a student, he got a draft notice. His therapist wrote a letter telling the draft board that any break in his psychiatric treatment would endanger his mental health, so he was classified 4-F.

Michael returned to Brandeis as an English major, taking a seminar taught by Angela Davis, who later became a prominent Black activist, communist, and philosophy professor. He was enthralled by guest lecturers such as poet Allen Ginsburg, anarchist writer Paul Goodman, and French artist Marcel Duchamp. But the most powerful speaker he heard was Malcolm X, who had recently broken with the Nation of Islam. “His message was totally new and astonishing to me” Michael writes. “In his tough, rapid-fire style, he stressed the origins of African culture in Africa and the need for Black people to stand up for themselves.”

In law school, Michael met a fellow law student, Margie Leinsdorf, and they got married during their last year. After graduation, she took a job as a criminal defense lawyer with Legal Aid and Michael got a clerkship with US District Judge Constance Baker Motley, the only Black female federal judge in the United States at the time. He enjoyed his clerkship, describing how Judge Motley “ruled with a combination of the law, her heart, and her life experience – especially her own experience of racism.”

One day, William Kunstler and Morton Stavis, two of the founders of CCR, rushed into the judge’s chambers. Michael had never met them before but knew their reputations as radical civil rights lawyers. They wanted to immediately quash a subpoena the government had served on Joanne Kinoy, the daughter of Arthur Kinoy, a law professor at Rutgers and another founder of CCR. The prosecutors claimed she knew the whereabouts of the Weather Underground.

Judge Motley agreed to hear the motion, and after reading the briefs, ruled in Kinoy’s favor on the grounds that the narrow form of immunity the government had offered her did not adequately protect her Fifth Amendment rights. Years later, Judge Motley recommended Michael for Columbia Law School’s prestigious Medal for Excellence, calling him “the ablest law clerk I have had in my tenure on the bench.”

The Kinoy episode planted the seed for Michael, and when his one-year clerkship was over in September 1971, he went to work at CCR. In one capacity or another, he would be involved with CCR for the next 45 years.

As part of a fact-finding team, Michael was dispatched to Attica and began collecting evidence.

On his second day at work there was an uprising at Attica prison in upstate New York, and this became his first case at CCR. Thirty-two inmates and nine guards had been killed. As part of a fact-finding team, Michael was dispatched to Attica and began collecting evidence. Then he helped draft a 25-page federal lawsuit, Inmates of Attica Correctional Facility v. Nelson A. Rockefeller, seeking an order from the federal court requiring New York to charge state officials with murder, manslaughter, and assault. And using a Reconstruction-era statute, they asked that the federal government prosecute the state officials for civil rights violations.

The defendants moved to dismiss the case. It would be Michael’s first appearance in court as a lawyer, and he spent days preparing for the hearing. When the case was called, the judge asked “What’s this case about?”

Michael explained that it was “about the state’s failure to investigate the role of officials in the Attica killings and beatings. Plaintiffs want to compel the state and federal governments to investi…”

Cutting Michael off, the judge said he had seen cases like this before. “There’s no right to compel an investigation or prosecution. Case dismissed.”

Michael was stunned, embarrassed and disappointed. CCR appealed and a three-judge panel took the case seriously. They wrote an opinion detailing the allegations and even acknowledging that several inmates had a right to bring claims of this kind, but in the end held that “the extraordinary relief sought [compelling prosecution] cannot be granted in the situation here presented.”

Michael calls Attica his first lesson in understanding the need to be “as radical as reality itself.” He saw the lawsuit as a necessary but not sufficient response to official wrongdoing and state violence. But even more than that, Michael’s reaction to Attica reveals his deep personal compassion for the victims of government abuse.

Over the years, a number of inmates at Attica completed their sentences and were released. Margie and Michael invited one of them to their cabin in upstate New York. As the man helped Michael cut wood, he depressed the trigger on a chainsaw and it flew out of his hand. The man apologized, explaining that he had never used a power tool before, having been in a juvenile home since he was nine, out for a short while, and then in prison the rest of his life until his release.

Michael never forget the incident – “circumstances that put him in prison and the utter failure of the state to teach him any skills, even using the most basic power tools, from which he might have earned a living.”

“We went to demonstrations and negotiated with police. We represented those in the anti-war movement who had been jailed, spied on, and beaten up. We defended soldiers court-martialed for resistance to the Vietnam War. We represented members of the Young Lords, Black Panthers…”

Michael’s memoir is filled with accounts of the lawsuits and political actions he pursued, enriched by his personal encounters with the real people whose lives he touched and the impact they had on him. Amidst all the civil rights lawsuits CCR was handling, as well as an appeal of Kunstler’s contempt citation during the Chicago Eight trial and the appeals of the convictions in that case, Michael describes what else CCR’s young lawyers were doing.

“We went to demonstrations and negotiated with police. We represented those in the anti-war movement who had been jailed, spied on, and beaten up. We defended soldiers court-martialed for resistance to the Vietnam War. We represented members of the Young Lords, Black Panthers, and citizens brought before grand juries investigating the rash of anti-war bombings and the leaks of the Pentagon Papers.”

In 1973, Michael left his full-time position at CCR to teach at New York University Law School while still litigating cases for CCR and on his own, including several cases in support of Puerto Rican independentistas. Meanwhile, he candidly describes the problems in his marriage at that time – the growing relationship between Margie and Kunstler, and a flirtation that was intensifying between him and a smart, strikingly beautiful lawyer, Kristin Booth Glen, who was married and had two young kids, and who taught a course at NYU. In the spring of 1973, Michael was invited to visit Cuba by the University of Havana Law School. Margie declined to join Michael, saying she needed to stay behind to work with Kunstler. Kristin agreed to accompany Michael. He acknowledges that the separation “was a chance to explore our relationships with potential new lovers.”

Months later, Margie got her own apartment and then moved in with Kunstler. Michael moved in with Kristin, but that relationship ended a few months later. Eventually, Michael and Margie got divorced and she married Kunstler. Michael describes how four decades after their divorce, he and Margie “remain the closest of friends,” and share very similar politics, “although she may be even more radical than I am.” They worked on cases together and gave “each other unstinting support.”

Michael stayed close to Kunstler, who continued to work with CCR until his death in 1995. “There was no one like him,” Michael writes; “no one who could so dominate a courtroom, no one who cared so little about money, and no one who influenced so many others to become radical lawyers.” Much of that could be said of Michael himself. No wonder he took the subtitle of his book from Kunstler’s 1994 autobiography My Life as a Radical Lawyer.

Michael writes that during the 1980’s he threw his “heart and soul into resisting the Reagan agenda,” believing that “legal work in the courts and political work outside the courts should go hand in hand.” As legal director of CCR, president of the National Lawyers Guild, and a grassroots movement activist, he “worked on many cases and campaigns to support budding revolutions in Central America and the Carribbean and to end U.S. intervention.” He made more than 30 trips to Nicaragua, roughly the same number to Cuba, and several to Grenada, El Salvador, Guatemala, Jamaica, and Costa Rica, as well as to Mexico where he met with exiled revolutionaries. “In retrospect, though it was often not successful,” he recalls, “I believe this work – always done in collaboration with other lawyers and activists – was the most important and fulfilling I have ever done.” It should be noted that if Michael had been able to take account of his life and career after 2000, he might well have included his extraordinary representation of detainees in the wake of September 11, 2001, and his courageous defense of Julian Assange as equally important and fulfilling.

Michael’s autobiography is no starry-eyed, romanticized account of his life and the people he encountered. Instead, he is remarkably candid and deeply self-reflective. He admits that during his solidarity work throughout the 1980’s, he often made mistakes that he now regrets. “My enthusiasm for revolutionary movements,” he admits, “sometimes blinded me to policies that were simply wrong, and made me intolerable of dissenters within those movements.” Referring, for example, to Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega’s “self-aggrandizement and opportunism,” Michael describes his realization that “revolutionary leaders, too, could be corrupt and ruthless. The truth I finally understood was that broad social movements and grassroots groups make change, not charismatic heroes. It is a mistake to encourage cults of personality or to place too much power in the hands of any individual.” Insights like this elevate his book and make it worthwhile reading for anyone open to learning from a such a decent, thoughtful person.

“My enthusiasm for revolutionary movements,” he admits, “sometimes blinded me to policies that were simply wrong, and made me intolerable of dissenters within those movements.”

In his mid-40s, eager to change his personal life, Michael joined a therapy group. He tells of one session in which the therapist turned to him and asked whether in ten years he saw himself still “serially dating, traveling abroad all the time, and living the way are you are now?” Michael responded: “No, I want to find a life partner and have children.” The therapist instructed him to go out with at least six different people and report back to the group.

Uncharacteristically, Michael did not question authority, and a few months later met a 32-year old video journalist named Karen Ranucci. By the summer of 1987, Karen was pregnant and they decided to get married. Karen designed the wedding invitation – a photo of a very pregnant Karen. But she’s pointing a wooden AK-47 at Michael, who has his hands raised. The caption reads “Shotgun Wedding.” They were married in January, 1988 and on April 5, their son Jake was born. They gave him the middle name Harry, in honor of Michael’s father. Michael writes, “I was a happy man.” On February 18, 1990, their daughter Ana was born, named after Michael’s mother and Karen’s grandmother. Throughout the 1990’s, Michael taught human rights law at Yale and Columbia, stayed involved with cases at CCR, and wrote two books, one with Bret Stephens entitled International Human Rights Litigation in U.S Courts and the other with Reed Brody entitled The Pinochet Papers, containing the legal papers and precedent-setting decisions that led to the arrest in the United Kingdom of Augusto Pinochet.

On September 11, 2001, while on his morning jog along the West Side Highway in Manhattan, Michael watched in disbelief as an airplane crashed into the North Tower of the World Trade Center. Its was 8:46 am. Seventeen minutes later, he saw a second plane slam into the South Tower. He checked on his kids and found that Jake, 13, and Ana, 11, were both safe, as was Karen. The chapter entitled Guantanamo is riveting. It is perhaps the best account I have read of how teams of lawyers, including Michael and his colleagues at CCR, mounted an unprecedented series of legal challenges to President George W. Bush’s War on Terror. As he had done so many times in his career, Michael jumped in, and by September 23 he had co-written with attorney Jules Lobel a comprehensive article for The Jurist, outlining why Bush’s plan to launch a unilateral war against Afghanistan would violate international law, including the United Nations Charter. On October 3, he made a speech at the NYC chapter of the National Lawyers Guild arguing that the 9/11 attacks “should not have been called and treated as acts of war by the government,” but instead were “a criminal act, a crime against humanity under international law – the mass killing of a civilian population.” President Bush did not heed Michael’s advice.

In November, 2001, the New York Times reported that CCR was ready to challenge Bush’s latest effort to detain suspected terrorists, hold them indefinitely without a criminal trial, try them before secret military commissions, and deny them habeas corpus. The story carried a photo of Michael and CCR legal director Bill Goodman, who was quoted as saying that his job was “to defend the Constitution from its enemies,” and right now the main enemies “are the Justice Department and the White House.” Michael and Goodman got plenty of hate mail accusing them of having “a vile hatred for this country.” One read: “You are a bald fat fuck. Go over to Iraq and let them cut your big ass head off, you idiot scum-sucking lawyer.”

Some CCR donors and Board members questioned whether the organization should represent alleged terrorists, since CCR’s usual clients were anti-war demonstrators, civil rights activists, and others with whom CCR agreed politically. But Michael pushed back, arguing that the government was “taking away the writ of habeas corpus, a key democratic right” and that in a “police state, there is no limit to the executive’s power to jail anyone he wants without court review.”

CCR agreed to enter the fray.On February 19, 2002, CCR and others lawyers filed three lawsuits on behalf of several detainees who had been captured, tortured and confined at Guantanamo. The book ably describes the legal theories and proceedings as these cases wound their way through the courts, often facing adverse rulings, until the Supreme Court, on November 10, 2003, agreed to hear oral arguments on April 20, 2004.

Michael called it “an extraordinary win.” The New York Times called it the most important civil rights case in 50 years.

Meanwhile, CCR had previously decided to simultaneously address the fact that the government had detained as many as 3,000 people, mostly Muslims, in US detention centers without bail or legal representation. On April 17, 2002, CCR filed a lawsuit, Turkmen v. Ashcroft, challenging the policy of imprisoning non-U.S. citizens who were awaiting FBI clearances, even though there was no proof they had ever done anything unlawful. The case dragged on for years but eventually, in November 2009, six of the plaintiffs obtained a $1.26 million dollar settlement.

The case involving other plaintiffs was still pending at the time the book was written. On June 28, 2004, while on a much-needed vacation with his family in Greece, Michael got the news that in a 6-3 decision captioned in the CCR case of Rasul v. Bush, the Supreme Court held that US courts had jurisdiction to hear petitions for writs of habeas corpus from Guantanamo detainees. Michael called it “an extraordinary win.” The New York Times called it the most important civil rights case in 50 years.

Michael and a team of lawyers recruited by CCR then set about to implement the Rasul victory. Within six months, they had 100 lawyers and eventually 600 working pro bono on behalf of hundreds of Guantanamo detainees. Michael writes that he believes “the response from these lawyers – who included Republicans and Democrats, progressives and conservatives – will be seen in the future as one of the great chapters in the struggle for fundamental rights in the United States.”

By the time Bush left office in January 2009, more than 500 Guantanamo detainees had been released. Michael believes that none would have been freed without the litigation. On the other hand, he expresses his profound disappointment that despite Barack Obama’s campaign promises and all the legal efforts, Guantanamo remains open. Sadly it is still open five years after Michael’s death with 40 detainees remaining under indefinite confinement, an enduring stain on the United States.

Michael writes that at “CCR we believe that we can continue to make a difference by fighting against preventive detention, torture, and other abuses at Guantanamo and secret prisons around the globe.” He believed Guantanamo will be ranked alongside the shameful concentration camps set up in the US for Japanese Americans. “Until that day,” he writes, “it’s the obligation of all of us to join in the ongoing struggle for basic constitutional and human rights.”

What Michael achieved in his career, including his key role in the historic Guantanamo litigation, would have been enough to establish him as one of the most important civil rights and human rights lawyers in American history. But he wasn’t done yet. In fact, the story of Michael’s work on the Julian Assange case is so important it is the very first chapter of the book entitled Truth Tellers. On April 5, 2010, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange released a classified gun-sight video of a U.S. Army Apache helicopter firing on unarmed civilians in Baghdad. The video, labeled “Collateral Murder,” had been recorded three years earlier, during a U.S. military raid that killed at least 18 civilians, including two Reuters journalists, and injured two children, as a U.S. gunmen can be heard saying “Look at those dead bastards.” The video had never before been seen publicly.

On July 25, 2010, Assange held a press conference in London to announce the publication of the Afghan War Logs, containing 91,000 secret documents providing a never-before-seen history of the Afghan War. Assange was fiercely criticized in the media and Michael anticipated that Assange and Wikileaks were going to need help. He was right. Yet again, Michael did not side idly by.

He explained that Assange and WikiLeaks were “facing a battle both legal and political,” because, as he had learned in the Pentagon Papers case, “the U.S. government doesn’t like the truth coming out” and it is going to come after him. “Come after me for what?” Assange asked.

“Espionage.”

He immediately contacted Len Weinglass, a brilliant lawyer who had spent his entire career representing political activists, including Daniel Ellsberg in the Pentagon Papers case. Michael sent an email to WikiLeaks’ website introducing himself, Weinglass, and CCR. He got a prompt reply indicating that Assange would like to meet them in London. On October 22, 2010, Wikileaks published the Iraq War Logs, in conjunction with Le Monde, Der Spiegel, the Guardian, and the New York Times, containing 391,831 U.S. Army field reports. Soon thereafter, Michael and Weinglass met Assange in central London in the apartment of Jennifer Robinson, one of Assange’s lawyer who was away at the time. They were joined by Mark Stephens, Assange’s British solicitor, whom Michael describes as “a frizzy-haired middle-aged man dressed in a striped suit with a broad flashy tie.” At this point, Michael’s account begins to read like a John LaCarre novel.

Weinglass came right to the point. He explained that Assange and WikiLeaks were “facing a battle both legal and political,” because, as he had learned in the Pentagon Papers case, “the U.S. government doesn’t like the truth coming out” and it is going to come after him. “Come after me for what?” Assange asked.

“Espionage.” This may well have been the first time Assange was alerted to this risk, having assumed he was beyond the reach of American law.

Weinglass explained that Chelsea (then Bradley) Manning would be charged under the Espionage Act of 1917 for leaking the secret documents, despite the fact that Weinglass thought she was a whistleblower, not a spy. He indicated that the government might also indict Assange under the same law. Michael explained that the government could seek an indictment, issue a warrant for his arrest, and request extradition. Assange asked a few more questions.

Michael and Weinglass offered to represent Assange pro bono with the support of CCR. Assange accepted the offer. Michael and Weinglass felt Stephens, who specialized in commercial law and had no experience with political cases or extradition, was not right for the job and he was replaced with a distinguished barrister whom Weinglass had known for many years.

Soon after returning to New York, Weinglass was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and died a few months later. Michael recommended several criminal lawyers and Assange chose Barry Pollack, a highly respected criminal trial lawyer based in Washington, D.C. The book does an excellent job in recounting the intersecting stories of the court martial of Manning, the explosive revelations by Edward Snowden, and the indictment of Assange. Until he died in 2016, Michael continued to serve as Assange’s lawyer. More than that they became personal friends. Michael visited him several times in London and writes how much he “admired his strength, his keen intelligence, and his unflappable courage.”

“My experience has taught me that the truth has a way of coming out, even when the most powerful government on earth tries to crush it.”

In one of the most candid and revealing passages in his autobiography, Michael is asked why truth tellers like Assange, Manning, Snowden, and others are so important to him. “The answer is that they have succeeded in doing what CCR and I have been trying to do ever since the so-called war on terror began in the wake of September 11, 2001.” He mentions the dozen or so lawsuits CCR filed “seeking to expose and end rendition, illegal drone strikes, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the torture at Guantanamo and other secret U.S. prisons.” But each time the government would tell the courts, “You can’t litigate this. National Security.” “We had reached a dead end.” And then all of a sudden the truth tellers told the truth. “With acts of great courage, they revealed to the world what this country is actually doing. They sparked a much-needed public discussion of the U.S. government’s secret, illegal, and inhumane policies. And they brought people into the streets. As a result, we’re seeing the unraveling of governments and corporations all over the world.

“My experience has taught me that the truth has a way of coming out, even when the most powerful government on earth tries to crush it.” This is why I miss Michael so much. We needed him during the Trump years and we need him now as the movements he helped build continue the work of ending endless war, dismantling white supremacy, and resisting authoritarian governments at home and aboard.

By June 2012, Assange had taken refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he remained for seven years. In May 2019, the Trump Department of Justice indicted him on 17 counts under the Espionage Act of 1917 and one count under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. On April 11, 2019, the new Ecuadorian government expelled him.

Outside the embassy, he was immediately arrested by the London Metropolitan Police Service on outstanding warrants, including a provisional warrant at the request of the U.S. government. Ever since, Assange has been incarcerated in HM Prison Belmarsh. In June 2019, the U.S. formally submitted an extradition request to the United Kingdom. In January 2021, a British judge denied the U.S. request for extradition on the grounds he was at risk of committing suicide. The DOJ has appealed that ruling and Assange remains in jail to this day.

The book ends by describing three important projects, which, in addition to CCR, serve as a living legacy to Michael’s life and career. In the summer of 2004, over lunch one day with his good friend of 25 years Michael Steven Smith, Michael asked how they could find a way to let people know what was really going on. Smith suggested a radio show. Jim Lafferty, president of the National Lawyers Guild chapter in Los Angeles, had been hosting a show on KPFK, the Pacifica station for Southern California. The two Michaels came up with a format called Law and Disorder and pitched it to WBAI, the local New York Pacifica station.

It went on the air in July 2004. They brought on two co-hosts, Dalia Hashad, a Muslim activist, who worked on the ACLU’s Campaign Against Racial Profiling, and Heidi Boghosian, a half-Armenian activist lawyer and executive director of the NLG. Over the years, Law and Disorder has featured a variety of prominent guests on a wide range of important civil rights, civil liberties, and political issues.

“One thing I have learned over the years,” Michael writes, “is that if we are going to create lasting change, we need informed, politically aware, and committed grassroots movements. We cannot rely on the mainstream media. We have to inform ourselves through independent media.” Seventeen years later, Law and Disorder is still going strong.

In June 2004, 60 Minutes released sickening photographs of torture being inflicted at Abu Ghraib by U.S. soldiers and the CIA. Michael was shocked. True to his nature, he felt he personally needed to do something about it.

In June 2004, just as Michael was helping create Law and Disorder, 60 Minutes released sickening photographs of torture being inflicted at Abu Ghraib by U.S. soldiers and the CIA. Michael was shocked. True to his nature, he felt he personally needed to do something about it. He talked to Peter Weiss, CCR’s vice president, who in 1982 had won the landmark Filartiga case establishing legal precedent for the doctrine of universal jurisdiction, under which individual countries could put on trial the perpetrators of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Michael and Weiss discovered that a 2002 law granted universal jurisdiction to German courts and they began working with Wolfgang Kaleck, a German criminal lawyer, who on November 30, 2004, filed a 160-page criminal complaint with a German prosecutor on behalf of CCR and four Iraqi detainees who had been brutally tortured at Abu Ghraib.

The complaint was against Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, former CIA Director George Tenet and eight other high-ranking officials. The book traces the course of the case until the prosecutor dismissed the complaint in April 2007, a ruling that was upheld on appeal. Undaunted, and to ensure that the U.S. officials would be judged in the court of public opinion, Michael and CCR published The Trial of Donald Rumsfeld: A Prosecution by Book in 2008. Inspired by what Michael and CCR had done, Kaleck left his law firm and with a small group of lawyers established the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), where he served as legal director and general secretary. Michael was chosen as board chair.

From 2008 to 2015, Michael flew to Berlin twice a year for ECCHR board meetings. The organization has grown to a team of 24 staff lawyers and 12 trainee lawyers, and it is involved in litigation and other projects in 50 countries. Since 2008, more than 400 human rights lawyers from more than 40 countries have volunteered or been trained at ECCHR. “I am very touched,” Michael writes, “that the torch is being passed to a new generation of enthusiastic, skilled, and radical international lawyers.” He adds that it is “reassuring to know that every day ECCHR and its alumni are continuing to work for human rights worldwide, providing the kind of legal advocacy that can and will make a difference.”

The third legacy project Michael inspired with his colleagues at CCR was Palestine Legal. “As difficult as it is for me to write this,” he admits, “over time I also came to understand that the Israeli’s government’s constantly repeated refrain that it wanted peace with the Palestinians was actually a false narrative.” He concluded that the “truth was that the agenda of Zionism … had always been to eliminate Palestinians from the Jewish state by any means, including terrorism.”

Stephen Rohde is author of American Words of Freedom and Freedom of Assembly; contributor, Los Angeles Review of Books; member of the Board of Directors of Death Penalty Focus and ACLU-SC; Steering Committee, Black Jewish Justice Alliance; Chair, Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace; and a retired civil rights and civil liberties lawyer.

Stephen Rohde is author of American Words of Freedom and Freedom of Assembly; contributor, Los Angeles Review of Books; member of the Board of Directors of Death Penalty Focus and ACLU-SC; Steering Committee, Black Jewish Justice Alliance; Chair, Interfaith Communities United for Justice and Peace; and a retired civil rights and civil liberties lawyer.

Rohde’s review and remembrance first appeared in the LA Progressive, and was reprinted with the kind permission of author Rohde, and publisher/editors Dick Price and Sharon Kyle.