AB 90, a bill introduced by California Assembly Member Shirley Weber, would ramp up oversight of the state’s controversial gang database, CalGang. The bill would require audits and other regulations to improve accountability and accuracy for the database, which is shared by law enforcement agencies across the state.

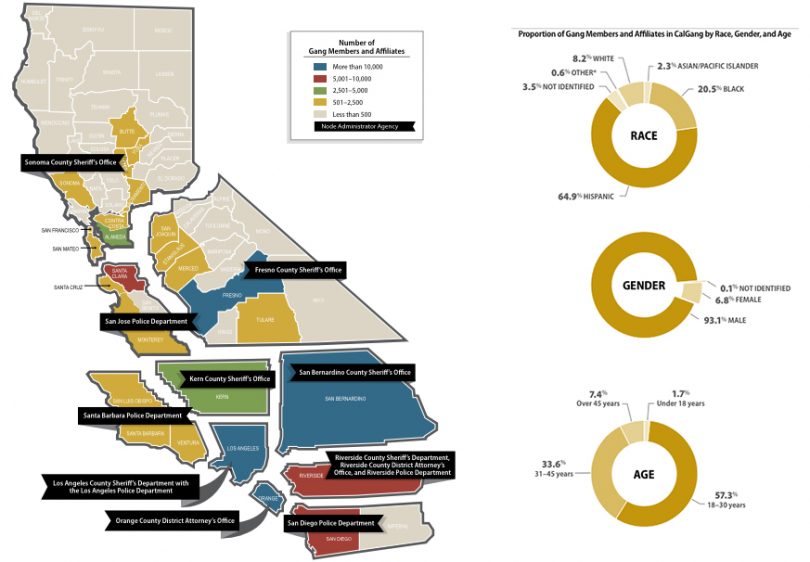

Oversight and administration of the CalGang Database would be moved to the California Department of Justice. Currently, according to the state’s DOJ, two oversight committees control the CalGang system. “The California Gang Node Advisory Committee deals with the day to day operations of the system, the CalGang Executive Board deals with the administrative, policy and sustainability issues.” State and local agencies operate the system.

The bill would block the operating agencies from sharing the database with federal agencies, like Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The legislation would also require that Californians are dropped from the gang database if, after two years, no new evidence has linked them to gang activity.

People who admit to law enforcement officers that they are gang members or who have gang-related tattoos are added to the database, but associating with known gang members and wearing clothing that might be gang-related also sends people into the CalGang database. Advocates say the vague criteria often have the effect of penalizing people of color for living in the wrong neighborhood. CalGang identification can also lead to inclusion in a gang injunction.

The non-profit Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is backing Weber’s bill. In an endorsement letter to Assm. Weber’s office, the EFF lauded the bill’s protections against database inaccuracies and mishandling. “The legislation would further ensure that Californians are removed from shared gang databases when no new evidence has emerged for two years linking them to gang activity,” EFF investigative researcher Dave Maass wrote.

Last year, Governor Jerry Brown signed a different CalGang reform bill by Weber, AB 2298, which requires that people be notified of their impending inclusion on California’s gang database. Once notified, those flagged for inclusion will have the opportunity to challenge the designation. The new law goes into effect on January 1, 2018.

Both bills were inspired by a 2016 audit from State Auditor Elain M. Howle, which found major errors in the database, and revealed a serious lack of necessary state oversight of a system that does not adequately protect the rights of the more than 150,000 people listed in the database. (Weber’s AB 90 The would put use of the database on hold until all of Howle’s concerns and recommendations regarding the database were resolved.)

The audit analyzed four agencies’—the Los Angeles Police Department, the Santa Ana Police Department, the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office, and the Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office—interactions with the database.

Howle’s office closely examined 100 individual CalGang profiles. Of those 100, the agencies could not support the inclusion of 13 of the people based on the database entry criteria.

A San Diego non-profit called Pillars of the Community (POTC) is gathering a team of attorneys who will volunteer their time to challenge CalGang designations for clients who believe they have been unfairly included in the database.

This week, the team of has filed discovery requests for 11 clients seeking documentation regarding why they were flagged as gang members.

PBS’s Claire Trageser has more on the new POTC endeavor.