EDITOR’S NOTE: When a kid in a Los Angeles County juvenile probation camp opened up about the world-stopping traumas of his childhood after being asked to name his favorite rap artist and rap song, the discussion that followed gave justice reform leader Alex M. Johnson his own epiphany about the healing power of art.

Bringing Arts Inside the Juvenile Justice System to Help Wounded Young People Heal and Thrive

by Alex M. Johnson

“Why am I trying to give, when no one gives me a try? Why am I dying to live if I’m just living to die?”

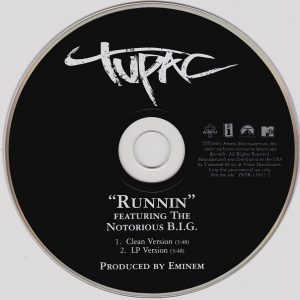

I didn’t write those words. Those are the words from the hook of a song written by 2Pac & Biggie called Runnin’.

The song resonates with me because of a time, a number of years ago, I was in a juvenile probation camp in Los Angeles County.

I hail from Los Angeles County where I am now president of the County Board of Education. LA County has the largest juvenile justice system in the nation, 14 probation camps, 3 juvenile halls. It used to serve 21,000 young people, with 17,000 young people on a formal probation in LA County.

I was sitting in a camp one day talking to a young man who looked like me, sitting across from him, having an awkward conversation. I didn’t know what to say, and he didn’t know what to say, as we tried to make small talk. Finally I asked him, “What type of music do you like?”

I love music. I love rap music, love jazz, classical, opera, you name it. So, we started talking about music, and he told me that his favorite rapper is 2Pac.

I said, “Great. Wow!”

I thought it would be one of these other rappers like Future, or someone like that. When he said 2Pac. I said, “Great.” We were starting to connect.

“What song do you like?” I asked him.” What’s your favorite rap song?”

He started by quoting those lyrics. “Why am I running to live, when I’m just living to die?”

It spoke to me and it continues to speak to me as I do some of the work that I do in Los Angeles County, in the state of California, working on justice reform.

This young man, this African American male, 16 or 17 years of age, was faced with what seemed almost like insurmountable traumas. He felt his life was over.

As I learned more about him subsequently, I found he been pushed out of school, had been in 12 or 13 schools, had been in almost an equal number of foster homes, had been diagnosed with every single behavioral disorder you could imagine.

I went back one day and had more time speaking with him. His sentence had been extended for one reason or another. This time, we had a longer conversation where he started to talk about his childhood. He told me he’d seen his mom get killed by his father. Then he’d subsequently seen his father get murdered as well. Now, this young man had no outlet. In a camp, in a facility, locked down, he was unable to express and to articulate the pain and the trauma and the hurt that he had felt for so many years.

His story is similar to so many others like him in LA County’s probation camps, and those 3 juvenile halls. Young men and women who have been rendered throwaways, whose stories are never told.

And so, I think about that story. I think about that young man, when I think about the arts, and about the power of the arts to heal, the power of the arts to change lives, the power of the arts to be transformative.

I think about the arts as a key critical strategy to dismantle and to change the school-to-prison pipeline.

A few years ago, the Children’s Defense Fund-California, where I formerly served as executive director, partnered with an organization named Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network (AIYN).

The partnership began after my good friend, Kaile Shilling, came to me with what I call a “Kaile idea.”

She said, “Why don’t we look into this program called Freedom Schools*, a five to six week summer literacy program, with some arts programming.”

And then she said, “Alex, why don’t you help pay for it through a sub-grant.”

And so, I said, “Sure.”

(I do whatever Kaile asks me to do most times.)

The Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network, for those who don’t know, is a collaboration of nine organizations that provide arts programming in our juvenile camps and halls in LA County. And so, they came in this particular summer with Freedom School, a literacy and reading program, with arts as the after school piece.

When we first bought Freedom School to the camps, there was complete skepticism from a lot of the probation officers. They didn’t think these kids wanted to do art. They didn’t think these kids had anything to say. They wanted to keep the status quo in place with young people marching around in formation listening to orders, which just rendered them silent and voiceless.

But when Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network came in, they did more than provide programming for the kids, they also trained the probation officers. Like I said, you had this cadre of probation officers who had been stoically steadfast in their resistance to anything progressive in the camps. If it wasn’t militarized, if it wasn’t about young people lining up, then they weren’t about it.

And they thought we were dumb for doing Freedom School. But, then AIYN brought the probation officers in to the space where the kids had been working, and the officers saw the artwork that the kids produced. They saw these beautiful murals on the walls. They saw and heard the stories that young people articulated through spoken word, and through poetry. They saw depictions of the lives that these young people had lived through stories, through drawings, through all these mediums.

And a conversion began to take place where these stoically steadfast officers began to actually change and see these young people for who they were—youth who are ready and able to thrive.

So, for me, when I think about the arts, when I think about creative youth development, I see it having the absolute potential to change lives, and to change the trajectory of systems.

That’s what we’re doing in LA County. We are trying to use the arts as a lever, as a vehicle to change a system that has been in place for decades by showing and telling these stories of hope, of healing, of redemption, of love, and of bringing in caring adults into the space. And we are modeling what is possible for the actors who have been in the system for so many years. It’s an amazing, amazing experience.

We have so much more work to do.

But I think the future is bright and there are lots of opportunities to help heal, to help rebuild, to help restore young people through the arts so that they can thrive.

Alex M. Johnson is the Managing Director for Californians for Safety and Justice, the President of the Los Angeles County Office of Education Board of Education, serves on the California Racial and Identity Profiling Advisory Board, the Board of Directors for the Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network, and the National Advisory Committee for the Creative Youth Development National Partnership. An earlier version of this essay first appeared in a speech Johnson gave at the 2017 Creative Youth Development National Partnership National Stakeholder Meeting.

*Freedom School is a youth literacy program originated by Marian Wright Edelman and the Children’s Defense Fund, inspired by the Freedom Schools of the civil rights era. In the summer of 2013, with the sponsorship of LA County Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, LA County Probation agreed to try out Freedom School in two of the county’s juvenile probation camps on a pilot basis—Fred C. Miller Camp in the hills of Malibu and Afflerbaugh Camp in the LaVerne. In 2015, the county expanded Freedom School into six camps, after a team from UCLA, USC and Vital Research evaluated the before and after effect of the program, and found that the reading scores of the kids involved went up an average of 51 points. Kaile Shilling and The Arts for Incarcerated Youth Network also entered in the picture in 2015, by helping expand the program to include arts programming for the young people involved. According to AIYN, the arts addition “increased the effectiveness of Freedom School through statistically significant increased participation and interest” in the program as a whole.