EDITOR’S NOTE: Although California as a whole has not been hit as hard as some other states by the nation’s life-destroying opioid scourge, certain of our counties——Humboldt, Inyo, Shasta, and others—are among the areas with some of the highest overdose rates in the nation.

Sam Quinones’ story below about the lawsuit brought by the state of Tennessee against Purdue Pharma—the company that introduced OxyContin to the American drug market in 1996—is not limited to a single region in its implications. To the contrary, what the lawsuit reveals about the cynical and deadly pattern of marketing employed by Purdue—when peddling its superstar drug—applies, sadly to every state in the union.

(Quinones, by the way, is the author of the critically-lauded “Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic,” a brilliantly reported, page-turner of a book that is absolutely the best—and best written—account of how this tortuous plague came into being. )

What a Newly Released Lawsuit Against Purdue Pharma Reveals About the Company’s Recklessly Aggressive Marketing of Its Favorite Opioid

by Sam Quinones

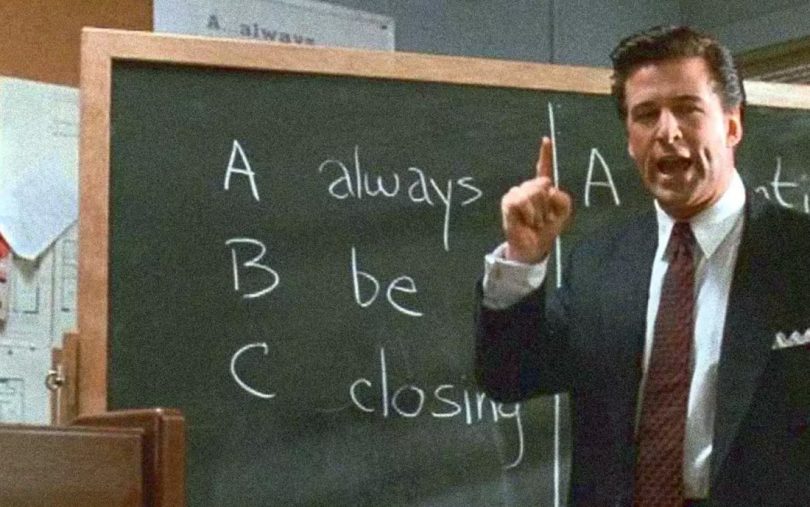

“Always Be Closing” is the motto that salesmen live by in the movie and play Glengarry Glen Ross.

If you haven’t seen the movie, do so. It’s great: Al Pacino, Jack Lemmon, Alex Baldwin, Kevin Spacey. It’s about an office of desperate sales guys hawking shady real estate investments. ABC — “Always Be Closing” — is the way each is supposed to approach every sales call.

It’s also a motto that showed up in Purdue Pharma sales notes and notebooks in Tennessee, according to a lawsuit against the company.

The suit was filed in May by the office of Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery. It alleges a lot of things, but in general that Purdue used deceptive marketing practices to push its signature drug, OxyContin. This took place, the suit alleges, between 2009 and 2012, well after the company and three of its executives pleaded guilty (in 2007) to a federal misdemeanor of false branding and paid a $634 million fine, while also committing to a series of measures to ensure they were not marketing to doctors who were prescribing unscrupulously.

The company moved to seal the lawsuit, but a judge in Knoxville recently decided against that idea, allowing the office to send me, and others, a copy.

In general terms, what I find interesting the lawsuit is how it displays the changes in pharmaceutical sales in this country, much of that coming during the life of OxyContin, though not due to it.

A new brand of sales

Up to the mid-1990s, drug salesmen in the United States were usually older men, often with backgrounds in pharmacy or medicine. They were often from the communities they sold to, knew the doctors they sold to, and became credible sources of information for those same doctors as medicine began to change rapidly.

Then the industry went another route. Those older folks were shown the door. In what can be called a sales force arms race, drug companies hired more and more reps. These reps were usually much younger, very good looking. They didn’t know much about they were selling but they have backgrounds in sales. They inundated doctors with visits and giveaways, of pens, calendars, lunch, sometimes trips for continuing medical education seminars. The companies were aware that by massaging a doctor’s staff, the doctor would soon be an easier mark.

Many companies did this. The numbers of sales rep rose through the 1990s from 35,000 nationwide to over 100,000 by the end of the decade. But other companies were selling blockbuster drugs to deal with cholesterol, hypertension and others. Purdue was among the few that used these techniques, and this enhanced salesforce (numbering eventually 1,000), to sell a narcotic painkiller.

“Always Be Closing” was, apparently, part of that push at Purdue. So, allegedly, was mention of the movie. All of this coming after the 2007 criminal lawsuit.

In Tennessee, (pop. 6.6 million people), the company made 300,000 sales calls to healthcare providers in the 2007-17 decade, during which time doctors prescribed more than 104,000,000 OxyContin tablets; more than half of those tablets were at the strongest doses the company made: 40mg and above.

Those of you who’ve read my book Dreamland know that, to me, supply is the crucial factor in this, and really in any drug scourge. What the lawsuit describes is a company hard at work at creating a vast new supply of opioids.

Company instructional materials pushed sales folks to “expand the physician’s definition of the appropriate patient” to which opioids might be prescribed; to “never give someone more info than they need to act”; and to develop a “specific plan for systematically moving physicians to move to the next level of prescribing.”

“We sell hope in a bottle,” said one guide for incoming salespeople, who were also instructed to encourage doctors to increase patients’ daily doses.

Doctors as marks

The lawsuit goes on to claim that Purdue sales reps in Tennessee were urged to make frequent sales calls, as evidence showed that that increased the number of prescriptions. According to the lawsuit, the company urged its salespeople to “focus on doctors who had more patients, less likely to have pain management expertise, and have less time to appropriately monitor patients on opioids.”

During these years, Purdue sales reps, according to the lawsuit, focused their efforts on primary care doctors, nurse practitioners and physicians assistants, whom the company “knew or should have known … had limited resources or time to scrutinize the company’s claims.” Together, people in those three professions prescribed 65 percent of all OxyContin tablets in Tennessee during these years. By 2015, Tennessee had the third-highest prescription rate of opioids in the country.

A major part of the lawsuit goes on to discuss specific examples of Tennessee doctors who were leading the state in opioid prescribing, often with signs that their practice was out of control or they were incompetent or unscrupulous, yet who were nonetheless aggressively marketed to by Purdue salespeople.

I’ve read Dreamland twice, just to make sure I absorbed all that was offered. The book is the product of arduous painstaking effort & should be mandatory reading for public policy makers, both legislative,law enforcement & in medicine. For those of you who have risked everything to stem illicit drug sales, this account of corrupt big Pharma, nieve or expedient/unethical physicians, pill mills (corrupt pharmacies) combined with Mexican tar heroin might well change your focus. The opioid epidemic is eminently fixable & this book serves as the map. Ask your local city council, board of supervisors, State & Federal representatives & law enforcement official if they have read Dreamland, if not insist they they do.