Researchers at Impact Justice have launched a first-of-its-kind study on prison food in the U.S., to be released this fall. The study will look not just at instances in which prison officials fed prisoners old, fetid food, but also at the short and long-term effects of prison food on the body.

Impact Justice will collect data from prisons across the nation, and interview justice experts, corrections officials, nutrition and public health experts, advocates, and prisoners and their families, focusing on the lived experiences of people who have spent time in prison.

“People who are incarcerated have a right to food that is not only nourishing but honors their humanity,” said Impact Justice President Alex Busansky. “We aim to transform the eating experience in prison to support people physically, mentally and emotionally in ways that ultimately will help them succeed when they return to their families and communities.”

Prisoners spend an average of three years (eating more than 3,000 meals) in lockup before returning to their communities. Yet, research shows that eating unhealthy foods for just four weeks can be seriously detrimental to a person’s health, in the long-run.

Cheap, highly processed, nutrient-deficient prison foods increase chronic disease and exacerbate preexisting conditions among incarcerated populations, past research has shown.

A separate Prison Policy Initiative report found that approximately 75 percent of all commissary purchases are of food and beverages, indicating “a widespread need to supplement the food” that prisons serve inmates.

“Prison and jail cafeterias are notorious for serving small portions of unappealing food,” the report says. “While the commissary may help supplement a lack of calories in the cafeteria (for a price, of course), it does not compensate for poor quality. No fresh food is available, and most commissary food items are heavily processed.” So inmates buy tons of snack foods and ready-to-eat meals. This is unsurprising, the report says, because “many people need more food than the prison provides, and the easiest—if not only—alternatives are ramen and candy bars.”

Through charging inmates for basic necessities, prison systems can levy a portion of the financial burden of incarceration back onto incarcerated people and their families.

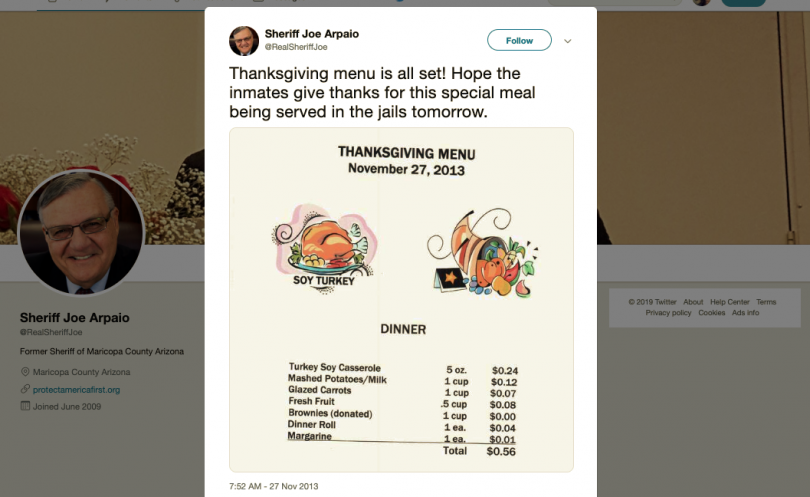

In Maricopa County, Arizona, in 2013, the notorious ex-sheriff Joe Arpaio bragged about serving the “cheapest meals in the U.S.” in his jails–two meals per day at a price landing between 15 cents and 40 cents each.

In 2017, LA Weekly got a look inside the kitchen at the California Institute for Men in Chino, where inmate workers prepare meals for their 3,400 fellow prisoners for $1.10 per person, per meal, each day.

The food is cooked in eight 150-gallon steam pots. The food situation at Chino is far better than in many parts of the country, where prisons are cutting costs by getting rid of lunch, or feeding inmates “vitamin drinks” to check off health requirements. Even in California, a state in which prisons spend more than most other states on food, newer prisons are getting rid of the traditional kitchen, choosing instead to serve inmates the equivalent of pre-packaged TV dinners.

(The Marshall Project offers a peek at what prison meals look like in several lockups across the U.S.)

Prison and jail officials’ counterproductive efforts to shave as much cost as possible from food budgets translates to increased healthcare costs, since prisoners are more likely to have chronic illnesses like high blood pressure and diabetes than people who are not incarcerated.

One creative way some prisons, including facilities in Oregon and Montana, are keeping meal costs low while vastly improving food quality is by launching gardening programs through which inmates earn gardening certificates while they grow produce for their fellow inmates.

“Food not only sustains us, but also communicates identity, relationships, and values,” said Leslie Soble, an ethnographer specializing in foodways at Impact Justice who is spearheading the study. “It is time to re-examine the message we are currently sending to and about some of the most vulnerable members of our society through the prison food experience.”

I think Witness la is trolling us with these stories, so ridiculously boring and banal. Guess this is what we get for smarting off and questioning the narrative too much. I can’t help but appreciate a troll (with the exception of cf of course) well played Witness la.

@Maj Kong, agree with for the most part. The use of Joe Arpiao is like using a glittering lure when fishing for bass during spawn. The jail menu for the Maricopa County Jail was used by Sheriff Joe as one of his symbolic representations of toughness & it played well to his constituents. There are other examples, such as found in the South wherein there’s a personal profit incentive for the Sheriff in food costs, not in a good way though. My experience with the LA County food services was one of clear excellence & pride of the culinary staff. I’m sure there are exceptions but I’d bet the majority of county food services are more than adequate.

Interesting how they will do a study of the food in prison that is regulated by Tile-15 and Tile -24. Which states how much protein, sugar, fat and all sorts of guide lines. The comment that inmates need a well balance nutritional meal and they will conduct a study. I wonder if the study will include what each subject of this study eats once he/she is out of prison. Will they collect the data on how many times they eat at McDonalds, Jack in the Box, Poppey’s chicken. How much alcohol is consumed with their out of prison diet. If you are going to judge or in this case conduct a comprehensive study, then do it right. Ask the subjects what they ate before prison and follow what they ate after prison. I think you find that they eat more “nutritious meals” while they are in prison.

I spent 15 years in Florida DOC for a non violent drug charge. I went to bed hungry every night and the meals they did serve were nothing but simple starch and soy.

Hello!!! I have a friend in prison. Eating TV dinners that say, ” only for institutions,”

Excuse me? Do you care to know where, then ask me personally. Otherwise I will make it my life’s work to blow this up, and save this exchange in the meantime. Have you seen the studies on long term health in the prisons? Yikes, you are making my heart and soul hurt. Go eat the food and study yourself. Unbelievable. Save!!!!!