By Wendy Sawyer, Prison Policy Initiative

Given the dramatic growth of women’s incarceration in recent years, it’s concerning how little attention and how few resources have been directed to meeting the reentry needs of justice-involved women. After all, we know that women have different pathways to incarceration than men, and distinct needs, including the treatment of past trauma and substance use disorders, and more broadly, escaping poverty and meeting the needs of their children and families. In recognition of these differences, and in an effort to reduce the harms of incarceration and the likelihood of re-incarceration, many prison systems have begun to implement gender-responsive policies and programs. But what’s being done to help women get the support they need to rebuild their lives after release?

A handful of programs have sprung up in communities around the country to meet the needs of women returning home: some founded by formerly incarcerated women themselves, some running on shoestring budgets for years, and all underscoring the need for greater capacity to meet the demand of over 81,000 releases from prison and 1.8 million releases from jail each year.

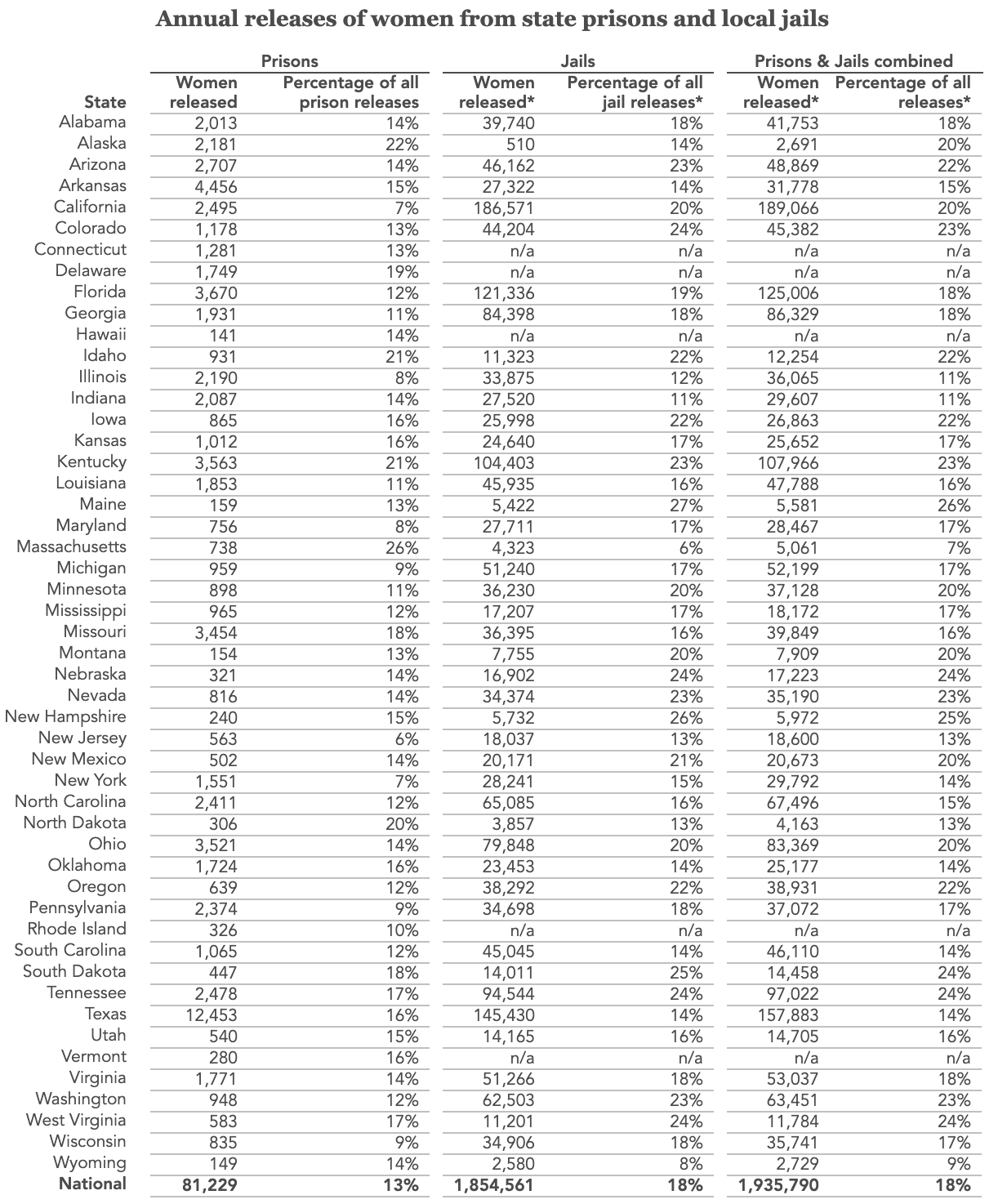

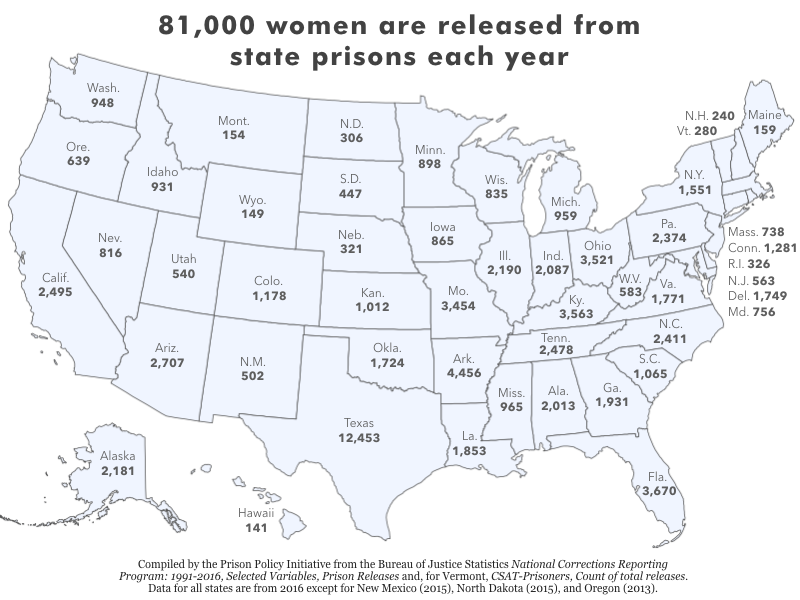

In 2016, about 81,000 women were released from state prisons nationwide, and women and girls accounted for at least 1.8 million releases from local jails in 2013 (the last year all jails were surveyed). While many people are released from jail within a day or so and may not need reentry support, jail releases can’t be overlooked, especially for women, who are more likely than men to be incarcerated in jails as opposed to prisons. (Moreover, jails typically provide fewer programs and services than prisons, so individuals released from jails are even less likely to have received necessary treatment or services while incarcerated than those in prison.)

Those figures mean that nationally, about 1 in 8 (13%) of all individuals released from state prisons – and more than 1 in 6 (18%) jail releases – are women. In 20 states, at least 1 in 5 (20%) individuals released from any incarceration (either prison or jail) is female. Fully half of all states release at least 1,000 women from prison annually; in Texas, it’s over 12,000 women per year.

As in other stages of the criminal justice system, most post-release policies and programs were created with the much larger male population in mind. But research makes clear that women returning home have “a significantly higher need for services than men,” and that reentry supports should be responsive to the particular needs of justice-involved women:

- Economic marginalization and poverty: As we’ve previously shown, formerly incarcerated women (especially women of color)have much higher rates of unemployment and homelessness, and are less likely to have a high school education, compared to formerly incarcerated men. These findings help explain why, in a 2012 National Institute of Justice (NIJ) study, 79% of women interviewed 30 days pre-release cited “employment, education, and life skills services” as their greatest area of need (followed closely by transition services). An earlier study (Holtfreder et al., 2004), found that poverty is the strongest predictor of recidivism among women, and “providing state‐sponsored support to address short‐term needs (e.g., housing) reduces the odds of recidivism by 83%” for poor women on probation and parole.

- Housing: A 2017 Prisoner Reentry Institute (PRI) report identified homelessness and the lack of stable housing as the biggest problem facing women in the New York City justice system, noting that 80% of women at Rikers said they needed assistance finding housing upon discharge. A 2006 California study found that 75% of formerly incarcerated women surveyed had experienced homelessness at some point, and 41% were currently homeless. Women who can’t secure safe housing may return to abusive partners or family situations for housing and financial reasons – a point echoed in interviews with paroled women in a study by Brown and Bloom.

- Trauma and gendered pathways to incarceration: The PRI report emphasizes the importance of gender-responsive and trauma-informed interventions for reducing recidivism among women. According to that report, such interventions should: provide a safe, respectful environment; promote healthy relationships; address substance use, trauma, and mental health issues; provide women with opportunities to improve their socioeconomic conditions; establish “comprehensive and collaborative” community services; and prioritize women’s empowerment.

- Family reunification: Most incarcerated women are mothers, and are frequently the primary caretakers of their children. The importance of family reunification – noted throughout the literature, by Carter et al.(2006), Brown and Bloom (2009), Wright, et al. (2012), the NIJ (2012), among others – cannot be overstated, especially given the trauma experienced by children when separated from a parent.

While the complexity of women’s reentry needs can be daunting, there are successful models in operation demonstrating how states, counties, and communities can best serve them. Notably, A New Way of Life Reentry Project operates eight houses in Los Angeles and is working toward expanding its model nationally. The program offers wraparound services including transitional housing, case management, and legal services to support women as they navigate reentry. Staff support women from initial reentry tasks like obtaining ID cards and applying for public assistance all the way through the process of regaining custody of children and finding permanent housing. Similar programs offering wraparound services exist in other cities, such as the Ladies of Hope Ministry’s Hope House in New York City; the Center for Women in Transition in St. Louis; and Angela House in Houston, which also provides programming tailored “to the health and psychosocial needs of women recovering from sexual exploitation.”

Frustratingly, despite their success, these programs lack the funding and capacity to serve all of the women who desperately need them: Angela House notes on its website that it can only serve 12 to 14 women at a time, but receives more than 300 applications every year. Unless state governments and federal agencies take action to grow the capacity of these service providers, hundreds of thousands of women every year will leave prison or jail without the resources they need to succeed. As lawmakers increasingly call for policy changes to help women in prison, they must not ignore the massive gap between the need and availability of women’s reentry programs.

*Note: The numbers in this table represent the minimum number and percentages of jail releases that are women. The actual numbers are probably greater, because a significant number of releases reported in the Census of Jails, 2013 are missing data on sex. (Nationally, 15% of all release records were missing this data.) The percentages of releases that are women, as reported in this table, were calculated based on the total number of jail releases, including those with no data on sex.

Wendy Sawyer is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative, where this story first appeared.

Sources and data notes for the map: Women make up 1 in 8 individuals released from state prisons each year, but the numbers vary widely between states. The additional 1.8 million women released from local jails annually are not shown on this map, because not all states have data available for jail releases, and in most states, a significant portion of reported releases are missing data on sex. See the table below for the available jail data.

Bureau of Justice Statistics National Corrections Reporting Program: 1991-2016, Selected Variables, Prison Releases and, for Vermont, CSAT-Prisoners Custom tables, Count of total releases. Data for all states are from 2016 except for New Mexico (2015), North Dakota (2015), and Oregon (2013).

Sources and data notes for the table: For prison releases, data are from the Bureau of Justice Statistics National Corrections Reporting Program, except for Vermont, which did not report release data by sex to NCRP. Vermont’s prison release data comes from BJS’ CSAT-Prisoners tool, and only includes releases of individuals sentenced to more than 1 year. Prison release data are from 2016 for all states except New Mexico (2015), North Dakota (2015), and Oregon (2013). Jail data are from the BJS Census of Jails, 2013, and are not available for 5 states (Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont) where the jail system is entirely integrated into the state prison system. In Alaska, there are a small number of locally operated jails not part of the state system, so available data reflect only the locally operated jails and not the entire jail population.

Jails and prisons are designed to hold people with pending charges, and then punish those who are convicted. Why are you so worried about who will help them when they get released? If the disincentive of being locked up isn’t enough to prevent recidivism, then they can go back and serve more time. Whether the convicts are male or female shouldn’t make a bit of difference.

If bleeding hearts would start preaching personal responsibility, they’d make a significant impact on their precious convicts’ lives.

Haaahahahaha…This PIG SOB just said something about taking personal responsibility when these f’n cops take zero accountability…shut the fuck up.

PS: THIS IS WHO WE ARE GIVING GUNS AND BADGES TO. This mentality is sick but we continue to empower them! Force change or no change!!!