A BREAKDOWN OF THE COSTS PASSED ON TO TAXPAYERS WHEN WRONGFUL CONVICTIONS OCCUR IN CALIFORNIA

Flawed convictions cost California taxpayers more than $282 million between 1989-2012, according to a report by researchers from UC Berkeley School of Law and the University of Pennsylvania Law School. Together, incarceration expenses, legal costs, and compensation for wrongful imprisonment accounted for the millions spent on convictions that would later be overturned.

The report examined 692 adult felony convictions that were overturned during that time period—although the total number is likely even higher, as there is no single comprehensive database on wrongful convictions in California. All told, the men and women affected by these mistakes spent 2,186 unnecessary years behind bars before their flawed convictions were overturned.

Costs relating to faulty homicide cases accounted for 52% of the $282 million cost.

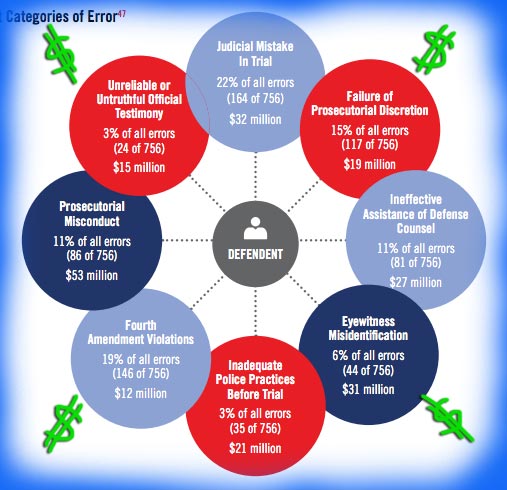

The biggest contributor to the enormous price tag was prosecutorial misconduct —including failure to turn over exculpatory evidence to the defense—cashing in at $53 million.

Nearly 20% of the erroneous convictions carried life sentences or life without parole. If the wrongfully convicted lifers served their full sentences, taxpayers would have needlessly spent millions more on their incarceration.

“As with airline safety and medical mistakes, we should be aiming for zero errors in our criminal justice system,” said Rebecca Silbert, the co-author of the report, who is now Senior Vice President at The Opportunity Institute in Berkeley. “The costs are too high to ignore.”

The report points to the human costs of wrongful convictions:

The taxpayer cost counts only a portion of the damage done by the errors catalogued here, as it cannot quantify the effect on those who were wrongfully or illegally incarcerated and their families. The individuals in this report were often incarcerated in the prime of their lives, in the time when they could have been getting an education, starting a career, and building a family. More than half were 35 or younger at the time of their conviction, and 21% were between 15 and 24. Their prosecutions are typically a matter of public record, leaving these future job seekers vulnerable to employer Internet searches that disclose the prosecution but not the dismissal. Their incomes are likely to decline after release from custody. They lost their right to vote while incarcerated in prison. Their children are stigmatized and more likely to suffer long-term emotional and behavioral challenges. Indeed, a parent’s incarceration alone increases the risk that his or her children will live in poverty or suffer household instability.

Such long-lasting effects may not always be quantifiable, but they are nonetheless a rallying cry for reform.

While many of the 682 convictions tracked in this report resulted in full exonerations, a large portion of the convictions were overturned due to errors or misconduct during the prosecution of the crimes.

“Errors in our criminal justice system, whether convicting the wrong person or obtaining a conviction that does not comply with the law, are costly to California taxpayers, crime victims, and defendants,” said co-auther John Hollway of Penn Law’s Quattrone Center. “Many people justifiably focus on the unacceptable convictions of those who are innocent, but we also have to look at convictions that cannot be sustained due to error, mistake, or intentional wrongdoing.”

Besides prosecutorial misconduct, other reasons for overturned cases included faulty eyewitness testimony (link), ineffective defense counsel, untruthful testimony by law enforcement and others during trial, civil rights violations, improper police practices before trial—for example: failure to read Miranda rights, and judicial errors, like jury misconduct and failure to seat an impartial jury.

The report points out that in 2006, the CA Commission on the Fair Administration of Justice put out a comprehensive report chock-full of recommendations on how to remedy problems with eyewitness identifications, perjurious testimony from informants, DNA and other scientific evidence, prosecutorial accountability, false confessions, and more. Ten years later, the majority of those recommendations still have not been implemented statewide, while the state’s criminal justice system repeats the same failures over and over again.

In 1991, my 12 year-old daughter was murdered. The man convicted to a life sentence was innocent. Throughout the trial I told the District Attorney he had the wrong person, that I had witness statements, etc. He actually got angry with me and stomped out of my house refusing the offered ride to the up-coming trial still a few months away.

The accused man’s father, and I, spent the next 24 years trying to secure his freedom. At his first Parle Heraing, we all attended and sopke on his behalf. He did get paroled.

I am now working to help three other persons with life sentences who’ve been wrongfully accused. One is through the Innocent Project of San Diego.

There are many people, more than the public is aware of, that are sitting behind bars with their lives ruined, for crimes they didn’t commit.

Only a few weeks ago, the Los Angeles City Council approved a multimillion $$ payment to Bruce Lisker, who spent over 25 years in prison on a wrongful murder conviction. Los Angeles was responsible for the improper actions of its employee, the LAPD detective who put together the case against Lisker.

Lisker’s conviction was not dependent on faulty witness identification testimony,it was gained through erroneous circumstantial evidence and witholding of potential exculpatory evidence pointing to another suspect.

Lisker’s exoneration is a rare case in itself, even more so because it did not come through efforts of an Innocence Project.

Bruce Lisker’s long journey back to freedom began when he inherited $100,000 while in prison. Lisker was able to hire an investigator to put in the leg work of reexamining the evidence used to convict him, including measurements taken at the crime scene.

We don’t know how many Bruce Lisker’s are spending lives in prison due erroneous or misrepresented forensics. We do know the public defender’s office has limited resources allocated to conduct an independent investigation, and they already begin with a disadvantage of time elapsed since the crime committed, while the police got there go when evidence was freshest.

What can we do when situations like this arise especially within our own families? Who can they contact , what can we do, who can help support them besides us?

^ what can we do when someone we know is in a similar situation but the innocence project might not be able to help?