Approximately 4.4 million (or 1 out of every 58) adults were on probation or parole in the United States as of the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ last updated count, at the end of 2018. To give some perspective, the number of people under community supervision is nearly double that of the incarcerated population of 2.3 million people. And probation and parole feed people back into the jail and prison systems, greatly contributing to mass incarceration, instead than alleviating it.

Just under half (45 percent) of people sent to state prison were on probation or parole at the time of their arrest. The majority of those violations were not for new criminal offenses, either. Rather, 25 percent of all state prison admissions were for technical violations of supervision, including missing appointments with parole and probation officers and failing drug tests, and not being able to maintain a job.

Thus, more than 50 current and former elected prosecutors and 90 current and former probation and parole officials, in partnership with Executives Transforming Probation and Parole (EXiT), issued a statement urging states and local governments to rethink community supervision. The group included more than a dozen supervision officials and district attorneys in California, including LA County District Attorney-Elect George Gascón and San Francisco DA Chesa Boudin.

Probation and parole, the justice leaders said, must be “substantially downsized, less punitive, and more hopeful, equitable and restorative.”

Conditions of community supervision vary but include regularly reporting to probation and parole officers, finding and keeping a job, staying within the state, not breaking additional laws, following curfew rules, submitting to random home visits, passing random drug and alcohol testing, attending anger management classes or other treatment programs, paying supervision fees, not changing residences without permission, not associating with family or friends with criminal records, etc.

These conditions easily conflict with each other. Having to carve out time for frequent appointments and drug tests, for example, can make it hard to hold down a job. And failing to show up for one meeting, or being unable to make one fee payment (just a few of many possible technical violations), can send a person right into the prison system.

The current status quo perpetuates racial disparities in the justice system and does not serve public safety or communities, according to EXiT and the coalition of prosecutors and justice leaders. “Probation and parole should promote development and success rather than trying to find failure,” they wrote. “Our system should provide hope for the future, not a pathway to incarceration.”

The group called for probation and parole terms that are “generally no longer than 18 months.” Supervision should also allow for “good time” credits that reduce the term length for milestone achievements like job retention and high school completion. Technical violations and many low-level new offenses should not result in incarceration, either, according to the group. States and local governments must also eliminate supervision fees levied against individuals and their families. Additionally, savings from cutting back probation and parole should be reinvested in community-based programs and supports. And justice officials must “seek, hear, and honor the voices of community members, families, and justice-involved individuals as equal partners in system reform.”

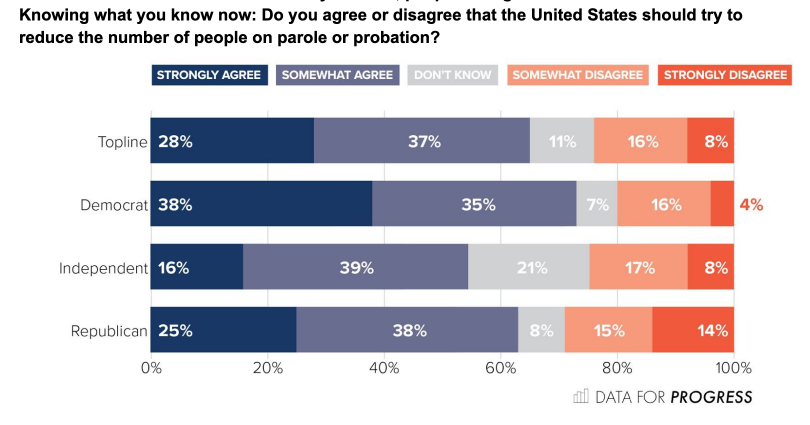

It appears that there is public support for addressing the nation’s mass supervision problem, as well.

In a new national poll of 1,164 likely voters, a majority of respondents said there were too many people on probation and parole, as well as in prisons and jails, and that the U.S. should try to reduce these justice system-involved populations.

A majority of participants also said they believed that the primary function of probation and parole should not be to surveil and supervise, but to provide supports and services that help people meet their employment, housing, and other needs.

Additionally, approximately 68 percent of those surveyed agreed that probation and parole should encourage positive life changes by offering term reductions for completing programs while on probation and parole.

While use of probation varies widely across state lines, some states, California among them, are already working toward substantial reforms.

In September, CA Governor Gavin Newsom signed AB 1950, which limited probation terms in most cases to one year for misdemeanors (previously three years for most crimes) and two years for most felonies.

The new law is expected to save the state hundreds of millions of dollars, and help reduce recidivism by shortening the length of time that an individual “might be subject to arbitrary or technical” probation violations that send them back to lockup.

There are states in which residents fare far worse than Californians with regard to mass supervision. While 1,018 out of every 100,000 Californians is serving a term of supervision, for example, twelve states have a supervision rate more than double that. At the farthest end of the spectrum, Georgia’s community supervision rate is more than five times that of California, at 5,369 out of every 100,000 people, or around one out of every 18 residents.

In an op-ed for USA Today, Miriam Krinsky, a former federal prosecutor and Executive Director of Fair and Just Prosecution, and Vincent Schiraldi, former Commissioner of the New York City Department of Probation, Co-director of the Colombia Justice Lab, and Co-Chair of EXiT, called for action during this “watershed moment,” amid protests and demands for a criminal legal system that will “better serve all members of our community.”

“Seizing that moment is going to require tackling and fundamentally transforming probation and parole systems that are fueling the very prisons and jails they were originally designed to decarcerate.”

So now that a 17 year old will not be charged as an adult, can kill your loved one, he or she will only serve 8 years in a locked up facility and then only be on probation for 2 years?