Implementation struggles have caused the price of California’s child welfare reform to soar by an estimated $101 million, according to a recent analysis from the California state legislature.

In a report released last month, the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office assessed California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s (D) January budget proposal related to the Continuum of Care Reform (CCR), an effort to move more foster children into home-based placements instead of institutional group homes. CCR was expected to pay for itself in under five years by banking on future savings from not placing as many children in pricey group homes and other congregate care settings.

The analysis found that implementation issues last year drove spending on CCR to $296 million, up from a projected $194 million. This year, as several CCR-related initiatives are sunsetting – including a fund for foster parent recruitment – the Legislative Analyst’s Office estimates general fund CCR costs will decline slightly, to $271 million.

Soon after the state started CCR in 2017, the state projected that the effort would be cost-neutral by the 2019-2020 fiscal year. But delays in licensing caregivers through the resource family approval (RFA) process have stretched that timetable.

“The continued prolonged RFA approval process … impedes the state’s ability to increase the number of foster caregivers and, accordingly, prevents the state from moving foster children out of congregate care settings … as fast as it otherwise could,” the report reads.

Other factors keeping the cost up include the slower-than-expected pace of congregate care reform, and the delayed implementation of an assessment tool for children entering foster care, according to the report, which said it expects CCR to carry considerable costs for the “foreseeable future.”

Under the state’s caregiver approval process, resource families (as both foster parents and relative caregivers are now known) have been stuck in limbo, waiting sometimes for months to get approved by a county after a child had been placed with them. That situation has improved slightly, according to the Legislative Analyst’s Office.

As of November 2018, about 55 percent of open resource family applications had been waiting for more than 90 days, down from more than 58 percent in June 2018. In that same period, the average number of days for these applications to be approved declined from 194 days to 182 days.

With the success of the state’s child welfare reform effort tied to the creation of more foster homes, a backlog of caregivers waiting to get licensed in the resource family approval process has made hitting the goals of CCR more difficult.

Last year, the state passed a law that provides $12.4 million to support caregivers who took in a foster child before gaining resource family approval with up to 180 days of financial support. However, starting in the 2019-2020 fiscal year, support will be limited to 90 days under the idea that the counties should be making progress at reducing their backlogs.

Under Newsom’s new budget, California is also proposing offering less assistance to counties to help with this task. The new budget offers $8 million to help counties shorten the caregiver approval process, down from $32 million from last year.

Use of congregate care placements in California declined by a robust 11 percent in 2018, part of a continuing drop that started in 2003. Under CCR, the state created an alternative to replace group homes, known as short‑term residential therapeutic programs (STRTPs). These placements are intended to be clinically driven residential facilities where foster youth in California are supposed to stay for short durations — only six months unless a county child welfare director agrees to extend the stay for another six months.

A greater share of young people is now residing in STRTPs rather than group homes, but fewer than expected have made the transition to living with families.

“A higher than originally expected proportion of caseload movement out of group homes is shifting to higher cost STRTPs as opposed to lower cost [home-based foster care] placements,” the report reads.

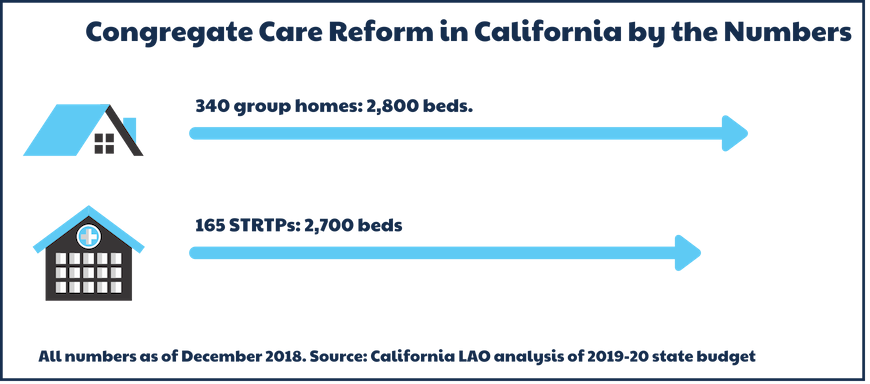

Over the current year, the Legislative Analyst’s Office notes that California currently estimates that 1,409 youth will transition from group home placements to STRTPs this year, almost 4.5 times higher than the estimate of 321 in May 2018. As of December 2018, there were 165 licensed STRTPs with a bed capacity of nearly 2,700 compared with 340 group homes that had a capacity of about 2,800 beds. Group homes must be completely phased by the end of this calendar year.

Another persistent issue has been the state’s ongoing delays with implementing an assessment tool that would determine payment rates for home-based care for the state’s foster children based on their level of need. Known as the level of care tool, it was supposed to have been rolled out across the state in March 2018 but so far it has only been administered to foster youth placed in placements through foster family agencies.

The tool has raised concerns from some advocates over whether it accurately reflects the elevated needs of many foster youth and how it might be used by a wide array of social workers in the state. There is also some concern about how the tool works with supplemental payments for high-needs youth that many counties offer to caregivers.

Jeremy Loudenback is the child trauma editor for The Chronicle of Social Change, where this story first appeared.

The Chronicle of Social Change is a national news outlet that covers issues affecting vulnerable children, youth and their families. Sign up for their newsletter or follow The Chronicle of Social Change on Facebook or Twitter.

Zzzzz…wake me when Families First is enacted.