Several California districts, including Los Angeles Unified, Compton Unified, and Oakland Unified, are experimenting with extra state money, via a school-funding formula still in its early years of implementation, to improve academic achievement among high-needs students.

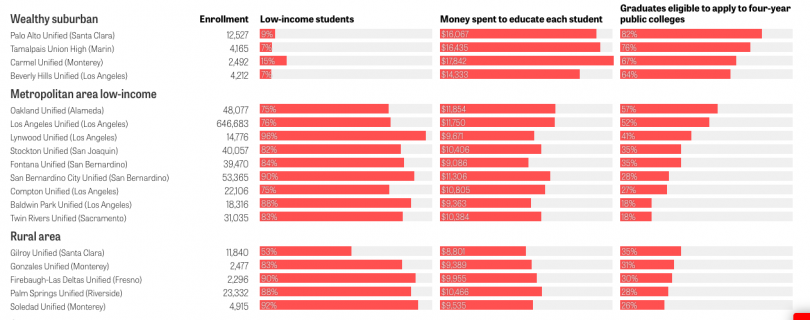

Prior to a 2013 funding approach overhaul, California’s education budget allocation was severely inequitable. More money was often given to affluent school districts, short-changing the schools—and kids—that most needed the state’s financial support.

California’s updated budget system, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), is a weighted funding approach that allows districts (rather than the state) to decide how a portion of their funding is spent. The new formula aims to level the playing field for high-needs students, including foster kids, who are severely underserved by school districts.

The LCFF sets aside extra money for high-needs kids—specifically kids from low-income households who qualify for a free or reduced-price school lunch, kids who are learning English as a second language, and high-risk foster children. The formula requires districts to set up goals and action plans for helping these vulnerable students transcend barriers with regard to attendance, suspensions and expulsions, and interactions with school police.

Susan Ferriss of the Center for Public Integrity chronicles California’s inequitable education history, and explains the ins and outs of LCFF, its potential and pitfalls, and the experimentation taking place at the local level.

(Ferriss has done some excellent reporting on the issue of discipline in schools, and making education in California more equitable and accessible for high-needs students.)

Compton Unified School District, where only one-fourth of the student population are eligible to apply to four-year state universities when they graduate, the district is spending $10.3 million on salaries and benefits to increase college-prep and career success and academic counseling, and $7.7 on books, supplies, and operating costs to beef up college and career prep services for its students.

Kern County, which in 2011, was named the state’s expulsion capital, is investing $2.1 million on implementing a restorative justice system and on providing teachers with “positive behavior” support training.

Los Angeles Unified, the largest district in CA, with more than 6,500 students in foster care, is putting $15.1 million of the 2016-2017 LCFF funds into hiring more counselors, social workers, psychologists, as well as ramping up student services. Another $15 million goes toward creating learning plans for LAUSD’s students in foster care.

Other pots of money are being used to implement (or expand) restorative justice programs to reduce unnecessary student suspensions and expulsions.

Some districts have struggled to earmark the extra money to help disadvantaged kids, as intended, however.

For example, 88% of Stockton Unified’s student population is considered disadvantaged, falling into one or more of categories indicated in the LCFF. During the current fiscal year, Stockton has set aside more than $2 million in funding on school police, safety officers, an alarm system, a crime data analyst, and a K-9 officer team.

And last year, the ACLU and Public Advocates filed a legal complaint last year against LA Unified for its allocation of $450 million to be used on special education, rather than disadvantaged kids. (WLA reported on the issue: here.)

The LCFF is still relatively new, and it may take some time to identify and eliminate weaknesses in the budget system.

To meet the LCFF’s goal of educational equity and improved student achievement, the state will have to hold districts accountable.

Next year, the State Board of Education is slated to release an “evaluation rubric” to determine whether local school districts are using the money appropriately.

Be sure to head over to The Center for Public Integrity to watch the full 17-minute video (previewed above) and to read Ferriss’ full story—it’s long, but certainly worthwhile.