STRENGTHENING THE FOSTER YOUTH BILL OF RIGHTS TO PROTECT AND EMPOWER KIDS IN THE CHILD WELFARE SYSTEM

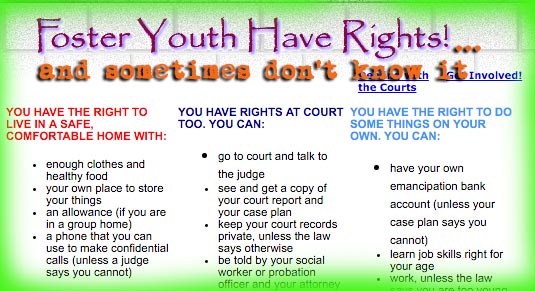

The Foster Youth Bill of Rights, enacted in 2001, says that (among dozens of other rights) foster children have the right to live in a safe and comfortable home, free from abuse, with enough clothes and healthy food, and the ability to visit with and contact siblings, parents, and other family members, and participate in after school and social activities.

Foster kids also have the right to refuse medication—a particularly noteworthy right considering California’s epidemic of doctors over-prescribing psychotropic drugs to foster kids. (For more on that issue, read Karen de Sá’s series, “Drugging Our Kids,” for the San Jose Mercury News.)

But in the 15 years that the law has been in effect, it has shown its weaknesses. Foster kids are sometimes not even aware of their rights, and often, ones that do know their rights don’t report rights violations out of fear that they will be removed from their homes or face retaliation by their caregiver.

A bill sponsored by Assemblymember Mike Gipson (D-Compton) would update and improve on the original Foster Youth Bill of Rights. A working group would be tasked with identifying the rights of kids in the child welfare system, and review the way foster youth are notified about those rights. The bill is sailing through the legislature without opposition. Anna Johnson, of the National Center for Youth Law, says she hopes the working group’s recommendations will look something like this:

– Establishment of a required form, filled out by the social worker and signed off by foster youth every six months to vouch that the youth were informed of their rights under the law. This proposal is intended to increase accountability in making sure information on the law is properly disseminated.

– Information on the law being made available on a more user-friendly website as well as on phone apps in order to reach its intended audience.

– Clearer outlines to foster youth of their rights to mental health services.

Glenn Daigon has more on the issue for The Chronicle of Social Change. Here’s a clip:

Findings in the 2013 Annual Report released by the Office of the California Foster Care Ombudsman demonstrate how the Foster Youth Bill of Rights is falling short:

“In some instances during interviews and presentations to youth in foster care, the FCO [Foster Care Ombudsman], found that not all social workers had reviewed the foster youth rights with dependent children as required by W&IC section 16501.1(f)(4). Children and youth in foster care reported to the FCO that they were not always aware that they had rights and that no one had informed them of their rights.”

The report goes on to say that some children and youth didn’t talk to their social worker or attorney about rights violations out of fear of being removed from their current home or that their caregiver might retaliate.

These problems with the law’s implementation were also reflected in an August 2015 hearing on foster group home reviews by the California Department of Social Services. When foster youth in group homes were asked if they or their peers would receive a negative consequence if they refused to take their psychotropic medications, 49 out of the 76 responded “yes.”

Vanessa Hernandez of California Youth Connection, a foster youth advocacy group, also highlighted the underperformance of the current law. “Caregivers were accessing ombudsman services at a greater rate than foster youth. This is a clear sign that the information was not being properly disseminated,” Hernandez said.

Tisha Ortiz, a Youth Advocate with the National Center for Youth Law, got a bird’s eye view of this problem. She was a client in the California foster care system from 2001 to 2010. During that time, she witnessed the following abuses against herself and/or her peers:

– Verbal abuse by group home staff, particularly when it came to disparaging overweight clients.

– The use of food as a weapon, i.e. the lack of adequate portion sizes at meals for some.

– Punishment for refusing to take medications in the form of stripping almost all personal belongings, extended lock– ups and isolation in rooms, and not being allowed to leave the group home for extended periods of time.

– Use of excessive manual labor, sometimes up to four hours of heavy physical work, as a punishment for some clients.

– A staff member putting his fingers down Ms. Ortiz’s throat in an attempt to force feed her medications.According to Ms. Ortiz, group home staff did not review the Foster Youth Bill of Rights with clients. She was only vaguely aware of the law through a poster. Ortiz felt that if more foster children knew about their right to complain to an ombudsman, their right to refuse taking medications and other legal rights, then these types of abuses in the system would be drastically reduced.

AM IN-DEPTH LOOK AT ORANGE COUNTY’S SUSPENSION RATES: MOST DISTRICTS ARE REDUCING SUSPENSIONS, BUT THE OC’S LARGEST DISTRICT IS DOING THE OPPOSITE

Thanks to a statewide push to reduce harsh school discipline, California has seen a 33% drop in out-of-school suspensions between the 2011-2012 and 2013-2014 school years.

For the most part, Orange County school districts’ suspension rates lined up with the state trend, according to a Voice of OC analysis of CA Department of Education and UCLA Civil Rights Project data.

Huntington Beach Union High reduced suspensions by 64% during that time period. And Santa Ana Unified, the largest of the OC’s 28 districts, cut suspension rates by 58%.

There were two districts that broke from the pack, however—Anaheim Union High and Tustin Unified—which reported a 203% and 45% spike in suspensions, respectively.

Anaheim’s suspensions rose in every category—weapons, drugs, violence with injury, violence without injury, disruption/defiance, and “other.” Specifically, suspensions for violence with injury jumped from 42 during the 2011-2012 school year, to 684 during the 2013-2014 school year. Willful defiance suspensions increased from 332 to 487. Tustin Unified showed a similar pattern: willful defiance suspensions went from zero during 2011-2012, to 259 during 2013-2014.

Los Angeles Unified, San Francisco Unified, and Oakland Unified have recently banned suspensions for willful defiance—a harmful catchall term for most anything that can pass as disruptive behavior, and is used disproportionately on students of color. In 2014, CA Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill banning expulsions for willful defiance for every grade, K-12, and willful defiance suspensions for kids in grades K-3. (We at WLA will be interested to see what that law, which went into effect in 2015, will have on school discipline numbers for the current school year.)

Here’s a clip from Voice of OC’s Thy Vo’s analysis:

It’s unclear why Anaheim and Tustin are going in the opposite direction from most other OC school districts. But we can consider a few factors that come into play.

Anaheim Union High is the only district in the county that saw increases in every category of suspensions. The largest increases were seen in suspensions for violence with injury — from 42 to 684; for drug offenses, which spiked from 74 to 462; and for willful defiance, which went from 332 to 487.

Suspensions increased in every category but weapons in Tustin Unified. The largest jump was in suspensions for willful defiance, which went from zero during the 2011-12 school year to 259 in 2013-14.

The increase in the two districts in willful defiance suspensions — a loose term for acting out in class — is surprising given that they have been dropping rapidly statewide.

Countywide, suspensions decreased in every category, with the 53 percent drop in willful defiance suspensions being the largest. Suspensions for violence with injury was the only category to increase, with 17 percent more suspensions in 2014 than 2011.

The increase was driven by a handful of schools where violent incidents are increasing: Anaheim Union High, Tustin Unified, Brea Olinda Unified, Los Alamitos Unified and La Habra City Elementary.

Nationwide, minority students, English learners and students with disabilities have the highest rates of suspension.

A 2015 Report by UCLA’s Civil Rights Project highlighting the “school discipline gap” found that in 2011-12, black students were suspended at the highest rates — 23 percent — followed by disabled students at 18 percent, American Indians at 12 percent, and Latinos and English learners at 11 percent. Meanwhile, 7 percent of white students were suspended that year.

This remains true in Orange County, where Latino and black students tend to be suspended disproportionate to their share of the student body.

LOS ANGELES TO PAY $750,000 TO A WOMAN ALLEGEDLY RAPED BY AN LAPD OFFICER

On Wednesday, the Los Angeles City Council approved a $750,000 settlement with a woman who was allegedly sexually assaulted by an LAPD officer while his partner stood as lookout.

In February, the two veteran LAPD officers, James Christopher Nichols, 44, and Luis Gustavo Valenzuela, 43, were charged with raping four women repeatedly between 2008 and 2011. “They’ve disgraced this badge. They’ve disgraced their oaths of office,” LAPD Chief Charlie Beck said back in February.

Prosecutors say Valenzuela and Nichols used threats of arrest to coerce their victims into compliance. Two other women allegedly raped by the Valenzuela and Nichols have also sued the city, and are each seeking more than $3 million in damages.

The two officers face life in prison, if convicted.

The LA Times’ Emily Alpert Reyes has the story. Here’s a clip:

Valenzuela and Nichols were placed on unpaid leave more than two years ago, after a halting internal investigation that was first launched when one of the women stepped forward. Criminal charges were eventually filed after an elite investigative unit took over the case.

The woman who brought the lawsuit said that in September 2009, Valenzuela and Nichols ordered her into their car as she was walking her dog, then drove the car to a secluded location where Valenzuela sexually assaulted her while Nichols kept a lookout in the front seat.

In the lawsuit, the woman said she later recounted her story to detectives after being arrested and brought to the Hollywood station five years ago. Police repeatedly told her not to hire a lawyer and urged her to be patient, according to her complaint.

The lawsuit alleges the city strung her along “to keep her quiet and avoid getting sued.” The woman hired a lawyer after reading about other lawsuits against the officers, her suit says.

The city agreed two years ago to pay $575,000 to settle one of those other cases, brought by another woman who accused the men of threatening her with jail unless she had sex with them.

Los Angeles faces additional legal challenges tied to the allegations against Nichols and Valenzuela. Two other women recently sued the city over alleged assaults by the officers, each asking more than $3 million in damages.