THE PUSH TO PROTECT KIDS FROM UNWITTINGLY WAIVING THEIR MIRANDA RIGHTS

by Jeremy Loudenback

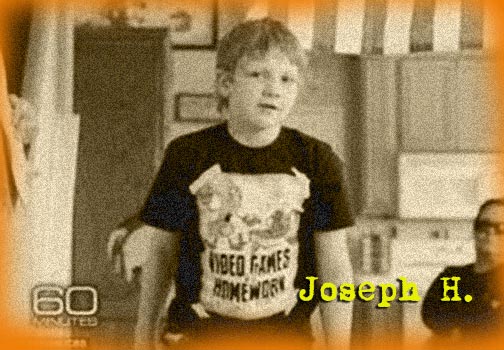

Early one morning in 2011, a 10-year-old Riverside boy named Joseph woke up, went downstairs and grabbed a .357 revolver from his parents’ bedroom closet.

He walked over to the living-room couch where his white supremacist father was sleeping off a night of drinking and shot him in the head.

“I shot dad,” the boy told his stepmother minutes later.

Alone in a patrol car later, Joseph again admitted to the grisly killing. He told the officer that he had been physically and emotionally abused by his father, a leader of the neo-Nazi National Socialist Movement. The night before, he said, Joseph’s father had threatened to take out all the smoke detectors in the home and burn the house down while the family slept.

As they drove to the police station, Joseph was worried that his sisters would be angry with him.

In 2013, then 12-year-old Joseph was found guilty of second-degree murder. At the end of a high-profile case that attracted lots of media attention, he was sentenced to seven years in juvenile prison.

But during interrogation, Joseph was permitted to waive his Miranda rights and to confess to the murder, despite a history of abuse at the hands of his parents as well as pronounced developmental issues.

When a police detective asked Joseph if he understood his right to remain silent, the 10-year-old replied that he did.

“Yes, that means I have the right to remain calm,” Joseph said.

Because no lawyer was present during the interrogation, the case sparked a legal appeal to the California Supreme Court.

In a four-to-three decision, California’s Supreme Court denied Joseph’s petition for review, leading Human Rights Watch, the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children and the Juvenile Law Center to file petitions to the United States Supreme Court to review the case.

PROPOSED LEGISLATION TO ADDRESS THE PROBLEM

In the wake of the Joseph H. case, as it is known, the California legislature is considering a bill that would place restrictions on how law enforcement officers can interrogate children and youth during a criminal investigation.

Under Senate Bill (SB) 1052, minors interrogated by the police would be required to speak with a lawyer before they could to waive their Miranda rights. Currently minors like Joseph are allowed to waive these rights even if they are too young or don’t understand what they mean. The bill would also provide guidance to courts about assessing statements given to the police by minors.

This is an auspicious year for Miranda rights. Fifty years ago, the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling in Miranda v. Arizona required police to inform suspects in custody that they have the right to remain silent and the right to consult with a lawyer before submitting to police interrogation. In 2011’s J.D.B v North Carolina case, the Supreme Court found that juveniles should receive expanded Miranda rights. But many now wonder if this was enough, and if there should be special provisions for children as young as Joseph.

Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has often ruled that children should be regarded differently under the law, in large part because of research on the socio-emotional and cognitive capacities of the adolescent brain. A developing brain, experts say, prevents youth from understanding the consequences of their actions and makes them susceptible to peer pressure and other forms of coercion.

But in the Joseph H. case, California courts deemed Joseph’s waiver of his Miranda rights was “knowing, intelligent and voluntary,” a legal standard that must be met for confessions to be admissible in court. This is the first time the state’s courts have upheld the waiver of Miranda rights for a child as young as age 10.

Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Irvine School of Law who has followed the Joseph H. case, feels the California court missed an opportunity to decide the age at which a child should be able to speak to a police officer without a lawyer or other friendly adult being present, such as a parent.

“You don’t let a 10-year-old make any legal decision, let alone one with potentially enormous consequences in waiving a constitutional right,” Chemerinsky said.

Introduced by California State Senators Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens) and Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles), SB 1052 would address the difference between adults and children by mandating that any child or youth have a conversation with a lawyer before a law enforcement officer would be able to question them. The attorney would be charged with making sure the minor understood their Miranda rights and the potential consequences of waiving them.

The bill has made it through the state Senate and is now moving through the Assembly. If it passes a vote before the Assembly Appropriations Committee on Wednesday, it could soon land on Governor Jerry Brown’s desk.

KIDS’ DEVELOPING BRAINS AND THE ABILITY TO COMPREHEND CONSEQUENCES

Elizabeth Calvin, an attorney with Human Rights Watch who has led the support for the bill, says the developing science of child and adolescent development clearly shows that children are not always able to understand the gravity of waiving their rights during an interrogation.

“There’s a growing recognition that our law has not caught up with science,” Calvin said. “[Children] have less of a capacity than adults to peer into the future and understand the ramifications of an action, and adolescents are still learning how to make those calculations.”

Advocates suggest that the constitutional rights enshrined in the Miranda warnings are applied to youth with little consideration about how developmentally different they are from their adult counterparts and how much they are able to understand the consequences of waiving these rights. For example, research suggests that children are more likely to be susceptible to coercion by adults, increasing the potential for false confessions.

Tim Curry, director of training and technical assistance at the National Juvenile Defender Center (NJDC), points to several studies that describe difficulties faced by children and youth in understanding the language of the Miranda rights.

Curry says that, like Joseph, many children are not able to understand what “the right to remain silent” means.

“We’ve heard everything, from that means ‘I have the right not to talk back’ or ‘I have right to be quiet and polite,’ not that ‘I don’t have to answer that question,’” Curry said.

The issue of whether youth fully comprehend their Miranda rights is also complicated by the fact that a large percentage of youth involved in the juvenile justice system have learning disabilities, making it more difficult for them to understand their legal rights.

Not surprisingly, SB 1052 has also drawn opposition from groups that represent district attorneys and law enforcement across the state.

According to Cory Salzillo, the legislative director of the California State Sheriffs’ Association, case law has made it clear that the court needs to take some special steps when a young person is being interrogated.

But a new law mandating increased contact with defense lawyers would mean increased costs at to law enforcement agencies in terms of time and resources. And the bill could have a “chilling” effect on the justice system by blocking or weakening voluntary confessions made by juveniles, according to Salzillo.

“Simply because [a statement to the police] was uttered before a consultation with legal counsel took place or if there was no consultation, the jury would have to view that with statement with caution,” Salzillo said. “It could cast doubt on an otherwise truthful statement.”

HOW OTHER STATES TREAT CHILDREN WITH REGARD TO MIRANDA WARNINGS

Standards for dealing with children in custodial interrogations vary widely across the country, but most states don’t look at juveniles any differently than they do adults, according to Curry of the NJDC.

About a dozen states allow children to waive their Miranda rights with the consent of a parent, though the age at which they are allowed to do so ranges from 12 in Washington to 16 in Montana and Iowa. In New Mexico, any confession by a child under the age of 13 is considered inadmissible in court under any circumstance. For children ages 13 and 14, confessions and other admissions are presumed inadmissible but prosecutors are allowed to appeal.

Like California, a few states are also now considering legislation that seeks to change Miranda language for children or provides protections for juveniles during interrogation.

The Illinois state legislature is reviewing a measure that would require a lawyer to be present when police question juveniles younger than 15 in investigations related to a murder or a sex offense. In Illinois, children age 13 and under cannot be questioned without a lawyer present in all types of investigations.

The bill would also include simplifying the language of the Miranda warning for children, something that a pending New York bill also hopes to accomplish.

While the California bill moves forward, advocates are also hoping that the Supreme Court considers the Joseph H. petitions. There’s no way to know whether the highest court in the land will take it up, but it will review the case in September.

“This is an issue about whether children and youth have constitutional rights because if you don’t understand your right and you can waive them, they’re not really rights,” said Calvin of Human Rights Watch.

Jeremy Loudenback is the Child Trauma Editor of The Chronicle of Social Change, where this story originally appeared, and which has kindly allowed us to reprint it.