California leads the nation in providing college education to currently and formerly incarcerated individuals, according to a joint study by the Stanford Criminal Justice Center and The Opportunity Institute.

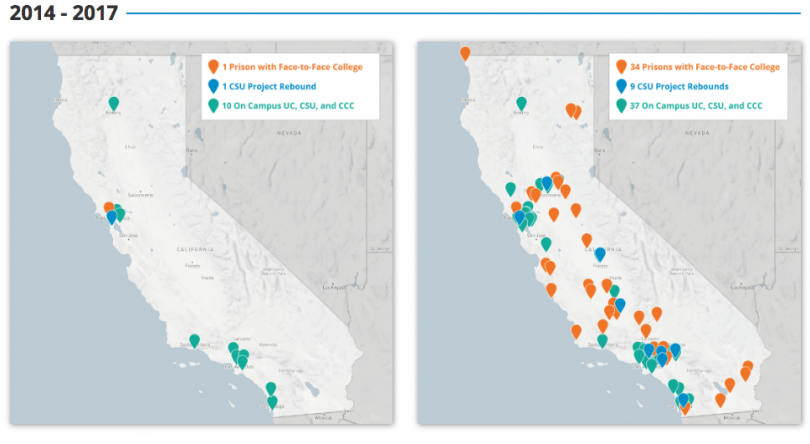

In 2014, the state offered career technical classes, as well as GED and high school diploma courses, but had little to offer in the way of college programs for currently and formerly incarcerated Californians. Just one lockup, San Quentin State Prison, offered a face-to-face college program, the Prison University Project.

The rest of the state’s prisoners seeking higher educational attainment were relegated to “low-quality, non-interactive correspondence courses with minimal educational support and guidance,” the report states.

Now, however, the state has more face-to-face college programs–in 34 out of 35 state prisons–than any other state, and should serve as a model for the nation, according to the report.

Nearly 4,500 individual incarcerated students—in minimum to maximum security prisons—are enrolled in CA’s college programs each semester.

“In just three short years, California has built a new generation of college students and graduates, creating onramps to redemption and prosperity for thousands,” said Debbie Mukamal, Executive Director of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center, and co-author of the report.

The report attributes the college program expansion to three state policies that could easily be replicated elsewhere in the nation.

The first is a law signed in 2014 by Governor Jerry Brown that allowed community colleges to conduct face-to-face courses in state prisons. The law also said that the schools would be paid for teaching incarcerated students as if they were being taught on campus.

There are also no undergraduate barriers to admission for people involved in the criminal justice system who want to attend CA public colleges and universities.

Moreover, just like every other low-income student in the state, students in lockup are eligible for the California College Promise Grant, which provides free community college tuition.

At the national level, incarcerated students are not eligible for federal Pell Grants, unless their school is one of the 67 colleges included in the Second Chance Pell Pilot Program. The number of students enrolled in face-to-face college classes for the fall 2017 semester (4,443) was higher than the total number of incarcerated students enrolled in the Second Chance Pell Pilot Program nationwide.

In 1994, U.S. Congress passed a punitive bill that made inmates ineligible for Pell Grants. “California’s experiences show what the rest of the nation could accomplish if the ban on Pell Grants for incarcerated students is lifted,” the report says.

“Early data shows that incarcerated students are doing as well as or better than their on-campus counterparts, including earning higher grades,” Mukamal said.

For example, in 2017, students in Cal State LA’s Communications class in prison earned an average GPA of 3.61. Their peers on campus earned a GPA of 3.25 in the same communications class taught by the same professor.

And while taxpayers cough up an average of $70,812 per year for each state prison inmate, it only takes a little over $5,000 a year to support a full-time community college student in California, according to the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office.

More than 95 percent of California’s prison population will eventually be released to return to their families and communities, according to a 2016 Public Policy Institute of California report, yet more than 60 percent of those released will be rearrested within two years.

Students who participate in education programs while in prison are 43 percent less likely to return to lockup after their release than their peers who do not participate in correctional education. The percentage is even higher if those classes are college courses, according to a Rand Corporation analysis. Incarcerated college students are 51 percent less likely to recidivate.

California isn’t just top of the class in offering college programs to prisoners. There are a growing number of support systems for formerly incarcerated college students in the state, as well. Approximately one-third of the 114 community colleges and California State University campuses in the state have services and/or student groups to help formerly incarcerated students complete their higher education goals.

Project Rebound, a well-known on-campus program for formerly incarcerated students, has expanded from San Francisco State University to eight additional CSU campuses, so far, with more campuses hoping to adopt the program.

“I was more scared to walk onto a college campus than onto any prison yard, but I was lucky to have a mentor who connected me with other students who had been incarcerated,” said Spencer Layman, who graduated from San Bernardino Valley College and is now a substance abuse counselor. “Some people will say that my success makes me an exception, but I am not. There are thousands of men and women just like me who can and want to turn their lives around. We just need to give them an opportunity to succeed.”

Nearly all of the face-to-face college programs offer full-credit community college classes that are “transferable, degree-granting courses” that allow students to continue their education upon release, and even at another prison, if they are transferred. (Cal State LA offers the only face-to-face program through which students can complete their full bachelor’s degree. The program operates in California State Prison, Los Angeles County, in Lancaster. )

Yet there are many more incarcerated students who are still in correspondence classes, waiting for face-to-face learning.

“We can’t stop now, “said Rebecca Silbert, Senior Fellow at The Opportunity Institute in Berkeley, and co-author of the report. “We owe it to ourselves and to those who are changing their lives to make sure that degree pathways in our public colleges and universities remain open to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated students into the future.”

[…] Walker, T. (2018, March 20) California: A national model for education behind bars. Witness LA. https://witnessla.com/california-a-national-model-for-higher-education-behind-bars/ […]